Posted on عفوا، هذه المدخلة موجودة فقط في English.

October 24, 2011

(English) Author Najem Wali revisits the magnificent house of Iraq’s first Minister of Finance, Sassoon Eskell, on the banks of the Tigris.

قراءة المزيد

Posted on

Posted on

JWeekly 8/12/2010

It has been nearly 60 years since Daniel Khazzoom left his native Baghdad — but the memories remain sharp and painful.

“The most painful part about writing [my memoir] was writing about Iraq,” Khazzoom said of the land where he spent the first 18 years of his life. “I did not want to remember it.”

Khazzoom, now 78, retired from U.C. Berkeley’s economics department in 2000 and spent the last eight years writing his just-published memoir, “No Way Back: The Journey of a Jew from Baghdad.”

The first half of the 256-page book focuses on his early life in Baghdad among the city’s 150,000 Jews, a childhood that began happily enough with six sisters and one brother.

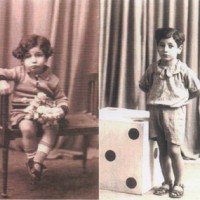

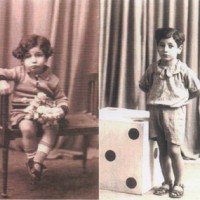

BAkhazoom

Split photos of Daniel Khazzoom in 1934 (left) and 1936.

That easy way of life changed in 1941, when hundreds of Jews were killed and wounded in a violent two-day pogrom in the Iraqi capital. Although a boy at the time, as Khazzoom grew up he yearned to make aliyah, and finally left for the Jewish state in 1951.

The remainder of the book explores the six years he spent in Israel — which were unexpectedly isolating and disappointing. “In Iraq, I walked with a badge — I was Jewish,” Khazzoom said. “That determined the attitude toward us, which was often very hostile.

“I thought that if I went to Israel, I wouldn’t have to walk with a badge,” he said. “Regrettably, we walked with the badge that we were Arab. We spoke differently, we were less uptight about Jewish observance. [European Jews] didn’t know what to do with us. The easiest way was to call us inferior.

“In Israel, Arab was the enemy. So we became the enemy. And I resented it.”

Though Khazzoom was “disenchanted” by the treatment of Sephardic Jews, he nonetheless joined the Israel Defense Forces and enrolled at Tel Aviv University to study economics.

In 1957, he became the first Israeli college graduate accepted by a Harvard University graduate school. While earning his doctorate in economics, he found himself feeling more at home in the United States than Israel. Recalling this realization still makes him cry.

“I felt like I was being pulled in opposite directions,” he wrote. “On one hand, my experience in Israel as a Jew from an Arab land and my shattered dream of making Israel my homeland; on the other my sense of duty to settle in Israel at the end of my graduate work.

“For the first time in my life, no one seemed to hold my differences against me.”

That Khazzoom was uprooted from Baghdad and felt ostracized in Israel has stayed with him throughout his life. It inspired him to serve as a board member of the Bay Area organization JIMENA, Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa.

After Harvard, Khazzoom went on to teach and do groundbreaking research at McGill University in Quebec, Stanford University and U.C. Berkeley, where he spent the last 12 years of his academic career.

In the 1970s, while at McGill, he worked tirelessly to help save the land of a tribe of indigenous Indians in northern Quebec from the Canadian government, which wanted to displace the Indians for a major hydroelectric project.

The issue went to court, and in part due to Khazzoom’s economic research on energy theory that supported the indigenous population’s claim, the Superior Court of Quebec ruled against the government. Khazzoom was named an honorary member of the tribe in 1973.

When he retired, Khazzoom moved to Sacramento where he is involved in three synagogues: Reform, Conserv-ative and Orthodox. “I am Sephardic, and in the Sephardic world, there is no division,” he said. “So I go to all three, though most of time I go to the Conservative synagogue.”

With help from his wife, Mairin, and a journalist friend, Ellen Graham, Khazzoom finished and published his memoir. He presented it July 25 at the first New York Sephardic Jewish Book Fair, organized by the American Sephardi Federation.

He hopes it’s the first of many opportunities he will have to share his story with readers.

“I wanted to put it on record how we lived [in Iraq], because ours is a vanishing culture,” Khazzoom said. “If 100 years from now someone wants to know how we lived, it’s on record.”

Daniel Khazzoom will speak about his book at 2 p.m. Sunday, Aug. 22 at Mosaic Law Congregation, 2300 Sierra Blvd., Sacramento.November 11, 2010

JWeekly 8/12/2010 It has been nearly 60 years since Daniel Khazzoom left his native Baghdad — but the memories remain sharp and painful. “The most painful part about writing [my memoir] was writing about Iraq,” Khazzoom said of the land where he spent the first 18 years of his life. “I did not want to […]

قراءة المزيد

Posted on عفوا، هذه المدخلة موجودة فقط في English.

February 28, 2012

عفوا، هذه المدخلة موجودة فقط في English.

قراءة المزيد

Posted on

Posted on

By KSENIA SVETLOVA

06/18/2010 19:35

Shmuel Moreh’s recollections of his childhood.

Talkbacks (5)

Almost 70 years after the culmination of violent Arab hostilities against the Jewish minority in Iraq, the on-line memoirs of a Baghdad-born Israeli professor are finding resonance among Arab and Iraqi readers and evoking a discussion on what used to be the taboo subject of the 1941 pogrom against the Jews of Iraq.

“The year 1941 was one of the most tragic years in the life of the Jews of Iraq,” wrote Hebrew University emeritus professor of Arabic literature Shmuel Moreh in the London-based and Saudi-funded on-line magazine Elaph. “It was a year of quick changes in the political, economic and social relations between Arabs (Muslim and Christian) on one hand and the Jews on the other,” continued Moreh, chairman of the Association of Jewish Academics from Iraq and recipient of the 1999 Israel Prize in Middle Eastern studies.

“As a child who lived in the modern, aristocratic, mixed quarter of al-Batawin in Baghdad and a student at the Al-Sa’doon Exemplary School, established in 1937 as a government mixed school that was founded for children of the Iraqi royal family, ministers, high-ranking civil servants and army officers, judges and secretaries, I was a mirror of the government attitude toward the Jewish citizens in Iraq.”

Moreh, who was born in 1932 and now lives in Mevaseret Zion with his wife, Kaarina, was one of three Jewish pupils who studied there among a majority of Muslim staff and pupils.

“The Jews suffered daily harassment, insults and mockery. A few days after the defeat of the Iraqi army attacks against the British military bases in Habbaniya and Sin al-Dhubban, Jews were attacked in the streets, they were searched for espionage equipment and taken to police stations for questioning if they did not bribe the police. Their houses were marked as Jewish by anti-Jewish organizations,” wrote Moreh.

“In April 1941, Faisal, the son of prime minister Rashid Ali al-Kailani, tried to blind the eyes of the writer of these lines by hitting him with a stick. This was a well-known punishment for Jews who dared to resist Muslims. Two months later, he was able to narrowly escape being lynched by Muslims and Christians at his school in revenge for the defeat of the Iraqi army.”

Soon after these emotional words first appeared in Elaph, letters in Arabic started pouring in to Moreh’s private mailbox, along with hundreds of talkbacks on Elaph’s Web site that revealed how deeply touched the readers were. Some of the writers identified themselves as Iraqi academics, journalists, researchers. They wrote about their feelings of guilt and shame but also about nostalgia and the good old days. Despite the bitterness of the painful memories of the persecution and the eventual exodus, they urged Moreh to come back, stressing that Iraq is missing its Jews.

“This story was written by an Iraqi Jew... It reveals his love for Baghdad, for the Tigris and Euphrates... No one can understand the pain of living as a foreigner, only those who have tasted it,” said one talkback.

“I am so happy for all Iraqi Jews that they are finally getting to see their old country and getting to see Baghdad. I feel bad that Baghdad does not look as good as the way they left it, but the Jews will make something out of it if they go back. They are great people and very smart, and I admire them,” revealed another one.

“Oh, the days of beautiful Baghdad, Baghdad of cultural tolerance and splendor, the days of music and theater... Where are the Iraqi Jews? Where are those days?” lamented the author of yet another talkback.

IT’S NOT every day that the readers of a popular Arabic media outlet have a chance for a close and personal encounter with an Israeli, a Jew, who has mastered Arabic better than many native speakers and who knows by heart the traditions and the origins of the traditions that form the daily life in Muslim Arab society. In fact, the decision of the Elaph management to print the memoirs of Moreh – born Sami Muallem – was so unusual that it made waves in many academic circles throughout the Arab world, as well as in the mass media in Iraq and beyond.

Some, mainly Palestinians, were furious, criticizing Elaph for the normalization of relations with Israel. But there were many others who relished Moreh’s beautiful and excruciatingly difficult Arabic, as well as his bittersweet memories of his childhood years in the posh Baghdad neighborhood of Al-Batawin.

The extraordinary relationship between Moreh and one of the most popular Arabic Web sites did not begin smoothly. When 'Abd al-Kader al-Janabi, a literary editor whose poetry Moreh used to teach at university, first approached Moreh with a request for an interview about his years in Iraq, he refused.

“He wrote to Nissim Rejwan, to Prof. Shimon Ballas and to myself asking for interviews. But I wasn’t interested. For me, Iraq is like an ex-spouse. Who would want to keep in touch with one’s former spouse? You just want to forget and move on,” Moreh says.

However, following some persuasion by his doctoral student Samir al-Hajj, Moreh agreed to be interviewed by Elaph.

“I told them many things – about my childhood, about my move to Israel and life here. I told them about my uncle who was the chief of police in a Baghdad police station and once met the king when he paid a visit to the station. He had the honor of lighting a match for the king, and he was so worried that the match would not burn well and could be interpreted as a bad omen for the new monarch, that he prayed in Hebrew to God that the match would burn,” he recounts.

“I also revealed that upon coming to Israel in 1951, I joined the army and in order to make a few extra bucks on the side, I started to write poems in Arabic and managed to publish them in Histadrut magazines. I was so proud of myself, mostly because in Iraq nobody would let a 16-year-old publish poetry in grown-up magazines.”

The interview in Elaph was published under the title “A soldier in the Israeli army writes Arabic poetry.” The interview was so powerful that the editor suggested publishing a series of his memoirs about life in Iraq. Moreh agreed.

“I wanted to achieve three things by writing these memoirs,” he explains. “First of all, to remind the world of the persecution of Iraqi Jews. If anyone thinks that life was a paradise for us there, he could not be more mistaken. We were called names, harassed on a daily basis, and I lived through this hell during all of my childhood.

“The second goal was to preserve the Jewish Iraqi dialect. Nowadays when I talk to Iraqis or write to them, many of them are astonished to be reminded of forgotten words their grandfathers once used. The Jews of Iraq kept the medieval Arabic, whereas the Muslims adopted the Saudi accent that was brought to Iraq by the Beduin who assimilated into the Iraqi populace.

“And, of course, the most important thing was the memory,” Moreh says. “I wanted to perpetuate the memory of the Farhud and the tragedy that we lived through. Some people say that the exodus of the Iraqi Jews was sped up due to the acts of violence carried out by Jewish Zionist underground organization, but this is baseless. I studied the issue closely. Ever since the Farhud – the horrible Iraqi pogrom that took place in 1941 when angry crowds lashed out at the Jewish community, robbing, raping and killing thousands – we were always afraid that something like this might happen again. But even before that, the Iraqi Jews were always subjected to humiliations and threats, and that’s what I meant to emphasize in my memoirs. I believe that by publishing my memoirs in Elaph over a period of three years, I achieved this goal,” Moreh says.

The Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Anti-Semitism at the Hebrew University, and the Babylonian Jewry Heritage Center in Or-Yehuda

recently published Al-Farhud: The 1941 Pogrom in Iraq, a book containing a series of papers on the theme, edited by Moreh and Zvi Yehuda. The work is a revised English edition of the Hebrew version, which was originally published in 1992.

“IN 1946 Jewish schools arranged an organized scout camp in northern Iraq. My friend Maurice Haddad and I were ordered to raise the Iraqi flag at the entrance of the camp. I saluted the flag and start singing the Iraqi anthem. I listened to Maurice sing and was horrified. He was cursing the flag, wishing it perdition. I was furious and tried to slap him on the face for insulting ‘our flag.’ He started weeping and shouted back, ‘Do you call it our flag? They killed my father when he tried to save my sister and mother from being raped.’ He was sobbing and murmuring all night long, ‘They raped my mother and sister and killed my father, and you tell me that this is our flag?’”

Today, after the three years of recollecting memories both sweet and painful, accepting and rejecting the past, writing, soul-searching and answering questions, the memoirs of Sami Muallem of Baghdad have reached their target audience – Arab intellectuals, historians, journalists and others who are reluctant to write off the Jewish chapter in the long history of the Arab world. The memoirs were reprinted in hundreds of various Arabic Web sites around the globe and have been read by hundreds of thousands of people. Moreh intends to translate and publish his memoirs in English and Hebrew.

The last chapter was published in Elaph in January 2010. However, the close relations that developed between Moreh and many of his readers continues to flourish. He is in touch with many Iraqi academics and journalists with whom he exchanges his views on the future of Iraqi Jews and their relationship with their old country.

As chairman of the Israeli Association of Jewish Academics from Iraq, Moreh is deeply concerned about the state of Jewish holy sites in Iraq and often uses his connections to prevent the ancient graves of Jewish prophets from being destroyed or desecrated.

And the yearning for the lost homeland is still there, despite all these years. The grief and the longing mingle together in poetic verses in canonical classical and modern Arabic, mixed with proverbs in Muslim Iraqi Arabic dialect.

Last night, my mother visited me in my dream!

Asking anxiously: “Haven’t you visited Iraq yet?

Have you forgotten to kiss the mezuzot?

To visit the tombs of our prophets?”

I replied: “Mommy! Surely I miss Babylon!

But our home in Baghdad has been destroyed!

And the way back is so dangerous and far beyond!

Everything there is in ruins,

Even the glory of the exilarchs,

The sanctity of our prophets’ tombs

And the glory of Haroun al-Rashid the great!

Today, on every inch in Iraq there are graves,

The waters of the Tigris and the Euphrates

As in the time of the Tatars,

Are flowing with blood and tears!

The masts are destroyed and the sails are torn,

So how it is possible to set sail and return?

(The poem “Departure” was published by Shmuel Moreh in February 2007 in memory of journalist Daniel Pearl. )

With reporting by Jonah Mandel.November 11, 2010

By KSENIA SVETLOVA 06/18/2010 19:35 Shmuel Moreh’s recollections of his childhood. Talkbacks (5) Almost 70 years after the culmination of violent Arab hostilities against the Jewish minority in Iraq, the on-line memoirs of a Baghdad-born Israeli professor are finding resonance among Arab and Iraqi readers and evoking a discussion on what used to be the […]

قراءة المزيد

Posted on عفوا، هذه المدخلة موجودة فقط في English.

October 24, 2011

عفوا، هذه المدخلة موجودة فقط في English.

قراءة المزيد

Posted on

Posted on  May 13, 2010

May 13, 2010

BAGHDAD — The United States has agreed to return millions of documents to Iraq, including Baghdad's Jewish archives, that were seized by the US military after the 2003 invasion, a minister said on Thursday.

The documents, which fill 48,000 containers, are currently being held by the US State Department, the National Archives and the Hoover Institute, a think-tank.

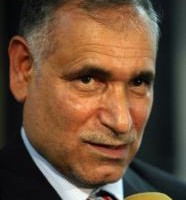

"We have reached an agreement with the United States, after negotiations with officials at the State Department and the Pentagon, over the return of the Jewish archives and millions of documents that were taken to America after the events of 2003," Deputy Culture Minister Taher Hamud said.

"The Jewish archives are important to us -- like the rest of the documents, it is a part of our culture and sheds light on the lives of the Jewish community," he told a news conference.

Iraq was home to a large Jewish community in ancient times but its members left en masse after the creation of Israel and the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948.

"Despite logistical, technical and political obstacles, we took the first step along the path to the return of the archives," Hamud said.

Iraqi National Archives director Saad Iskander told AFP in October that some 60 percent of the archives, amounting to tens of millions of documents, were missing or had been damaged or destroyed as a result of water leaks and a fire at a storage centre in the aftermath of the invasion.

Iskander added at Thursday's news conference that in addition to the Jewish archive many of the documents related to executed dictator Saddam Hussein and his banned Baath Party.

"There is a special archive about the Baath Party that was moved to the United States," he said.

"The CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) and the Pentagon studied it to find a relationship between Saddam and Al-Qaeda, terrorism, weapons of mass destruction and human rights violations."

Mohsen Hassan Ali, the culture ministry's associate museums director, said US forces had found damaged and water-logged documents in the basement of government buildings following the 2003 war.

"Despite our refusal, the containers were sent to the United States," Ali said.November 11, 2010

May 13, 2010 BAGHDAD — The United States has agreed to return millions of documents to Iraq, including Baghdad’s Jewish archives, that were seized by the US military after the 2003 invasion, a minister said on Thursday. The documents, which fill 48,000 containers, are currently being held by the US State Department, the National Archives […]

قراءة المزيد

Posted on

Posted on

Chicago Tribune - October 31st, 2010

Damaged during the U.S. invasion and shipped from Baghdad to Washington for preservation, a collection of antique Torahs and other material faces an uncertain future. Back to Iraq? Or to Israel?

Reporting from Baghdad —

A propaganda pamphlet written by Saddam Hussein's uncle and published in 1981 summed up the dictator's attitude toward Jews: It's titled "Three Whom God Should Not Have Created: Persians, Jews and Flies."

Under Hussein, the anti-Semitic Iraqi regime confiscated property and imprisoned and attacked Jews, all but eliminating the remains of what was once a thriving community.

Thousands fled, mostly to Israel and the United States, leaving Baghdad's Jewish quarter nearly empty, its masonry crumbling and its Stars of David dimmed by dust and time. Today, fewer than 10 Jews remain, and they keep a low profile, refusing to meet with outsiders.

But now a trove of rare Jewish books has ignited a battle between Iraqis who want to claim Judaism as part of Iraq's history and members of the Iraqi Diaspora who balk at entrusting their heritage to a country still more at war than at peace and where hostility to Jews remains widespread.

In the wake of the 2003 invasion, U.S. forces found a collection of confiscated antique Torahs, rabbinical Bibles and other documents in Baghdad. American authorities shipped them to Washington, where they remain.

Saad Eskander, the director of Iraq's National Library and Archive, says the collection belongs in Iraq. He said he was negotiating with the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, but if those talks failed, he would probably work with international organizations to take the case to U.S. courts.

"Jews are Iraq's oldest community. They are a significant part of the history of establishing Iraq," said Eskander, who helped rebuild the National Library after it was reduced to rubble by fighting and looting.

Jewish groups in America and Israel, however, have raised concerns about the safety of the collection if it were returned to Iraq.

"We fear the documents might be lost forever to Iraqi Jews," said Eric Fusfield of the B'nai B'rith international Jewish organization, which wrote to Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton this year calling for an immediate bar on the return of the documents.

"The Iraqi government should be commended for trying to preserve the Jewish legacy … but these are Jewish communal properties first and foremost."

State Department officials in Baghdad declined to comment beyond saying that negotiations were ongoing and that they hoped for resolution soon.

The collection was found soaking in dirty water in the basement of an abandoned Iraqi intelligence building shortly after U.S.-led forces blazed into Baghdad and toppled Hussein.

With logistical help from Iraqi exiles and then-ally Ahmad Chalabi, U.S. troops fished out the books and papers. Photos taken at the time show handwritten Hebrew texts spread out on the lawn outside the office, drying in the Baghdad heat.

A team from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration was dispatched to Baghdad, and the papers were put in 27 metal trunks in a refrigerated truck to stop the spread of mold. The military flew them to the U.S., where the fragile papers were freeze-dried at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

A deal was struck between Iraqi authorities and the State Department that the collection would be shipped back in two years. In 2005, as sectarian violence escalated, that deadline was extended for another two years, then allowed to lapse.

"We at the National Library raised the alarm and demanded their return to Iraq. They are Iraqi cultural property," said Eskander, who traveled to Washington this year to negotiate with the State Department and meet with representatives of the large Iraqi Jewish Diaspora.

Although he insists that he would digitize the collection, make it available online and add other important Iraqi Jewish works to it, some in the Diaspora remain skeptical of the books' long-term safety.

Shmuel Moreh, a professor of Arabic literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, left Iraq in 1951, along with hundreds of thousands of Jews who were victimized in the wake of the creation of Israel. He believes that all Jewish documents from Iraq are vital, and would like to see them in Israel.

"We need the documents to learn about history," he said. "We couldn't take any documents from Iraq when we left."

Although he felt that the Iraqi government had every right to claim the documents as their own and said he would be happy to work with good copies of the documents, he expressed doubt that Iraq had the skills to read the rare Judeo-Arabic scripts or the facilities to conserve the archive.

The collection, now kept in cold storage, would be subject to Iraq's flickering electricity supplies and to the still-considerable risk of bombs, thieves and institutional disarray.

A trip to the Babylonian section of a museum in Berlin, filled with archaeological treasures taken in the 19th century from what is now Iraq, had made Moreh believe the documents would be safer elsewhere.

He was accompanied by a group of Iraqi academics who admired the magnificent winged bull sculptures of the early Assyrian civilization displayed in the museum. Had they remained in Iraq, they would probably have been pocked with bullets or stolen, he said.

Moreh said: "Even these educated people said, 'What luck that the Germans took all this and kept it in such a way. They saved my civilization.'"

Fordham is a special correspondent.November 11, 2010

Chicago Tribune – October 31st, 2010 Damaged during the U.S. invasion and shipped from Baghdad to Washington for preservation, a collection of antique Torahs and other material faces an uncertain future. Back to Iraq? Or to Israel? Reporting from Baghdad — A propaganda pamphlet written by Saddam Hussein’s uncle and published in 1981 summed up […]

قراءة المزيد

Posted on

Posted on

By PEGGY CIDOR 04/30/2010 19:40

On the eve of the Second International Writers Festival, Eli Amir looks forward to discovering other authors’ secrets

The International Writers Festival of Jerusalem is taking place this week at Mishkenot Sha’ananim. It will also be celebrating the 150th anniversary of the decision of Jewish families to leave the overcrowded Old City and build new neighborhoods around it, one of them being Mishkenot Sha’ananim itself.

More than 20 writers from across the globe have confirmed their participation in the festival, where they will meet some 40 local authors. Some less common encounters will also be featured, such as meetings between authors and musicians. Old and new, tradition and renewal will be present at this prestigious gathering, which is also a way to remind locals and foreigners that Jerusalem is naturally associated with books.

Among the Israeli authors participating will be Eli Amir, who fled Iraq with his family when he was a child. In his books, he has vividly described his experiences as a Jewish youth arriving from an Arab country and culture into the Ashkenazi-dominated kibbutz and Zionist environment that prevailed here in the early 1950s. His latest book, The Dove Flyer, is the first in a trilogy reconstructing his childhood in Baghdad. Scapegoat recalls his early years as a teenager in the ma’abarot, and Jasmine recounts his youth in Israel. Recently, Scapegoat and The Dove Flyer were translated into English.

Amir, 72, for years the head of the Youth Aliya organization and a social activist identified with the Labor Movement, lives in Gilo. He strives to acknowledge the problem of immigrants from Arab countries, whose culture was considered to be inferior for years. He is involved in numerous projects to promote the Oriental culture and history.

What do authors look for in such festivals?

It is about the encounter with foreign writers. For me, it is an opportunity to meet the people behind the names written on the books I read and love. It is important because each of us believes that the “other” knows the secret or holds the key to the secret – because writing is a sort of a secret or a miracle happening in front of our eyes, so we all look for the secret of how to do it. I come to meet them, and somewhere in my mind, in my imagination, I hope I will find the writer who has it. Perhaps I could steal it from him? But sometimes it can also be disappointing because you come to discover someone you’ve read, and there you meet somebody who doesn’t measure up to your dreams or your imagination. It can be very frustrating.

What else do you look for?

You want to find out about the others’ sources of inspiration.

Do you have a key to these sources?

Yes, of course. I have my keys, I have my secret. But when I attend these encounters, I come without it. I come as a reader. I leave my writer’s hat behind. I come as I am. I sit among the public, listen to what is being read, mingle as part of the public. I find it enchanting.

Who else attends?

It is very intriguing to see the people who attend. Readers and the curious; people who want to touch those who know the secret of making a story come through, dreaming they might be touched by some grace and obtain for themselves the key to that secret. You also meet those who read your books very seriously, and they have all kinds of things to say – criticism, appreciation, suggestions. Some of them, in fact, bring you their own story, hoping it will get the appropriate “treatment” in your hands.

Do you like that feeling?

I love it! Friendship grows from there – ties, acquaintances between people, between writers and readers. It opens doors. And on top of that, it allows for encounters with decision-makers, critics and media people. Think of it – it is an exciting occasion to show such a beautiful face of Israel, not to mention revealing the incredibly wide range of literature we have here – beyond anything that exists anywhere else.

How can you explain the extraordinary amount of literature that is published here?

We are the first generation of immigrants; the urge to tell our story is tremendous – the need to leave our footprints in the sand of the immigration waves. Some of us have gone through horrible stories. Our writing is our shelter. It is also a time when we see the end of the dynasties: I was Fuad Elias Khalaschi. Today, I am Eli Amir. This is also because nobody could �pronounce my name correctly, so I got sick of it and changed it. You know, my eldest son read my most recent book while he was away on a trip. When he came back, I went to meet him at the airport. The first thing he said to me was, “Dad, I read your book. Now I know who you are.” It was a unique moment. And, of course, the tremendous tension in which we live here – this also ends up as a large harvest of writing.

When your most recent book The Dove Flyer was released, Amos Oz declared that Arab literature wouldn’t be complete until the book was translated into Arabic.

There were enthusiastic reviews in the Western media; but October, the major Egyptian literary magazine, compared it to the work of Naguib Mahfuz. It is a book about Baghdad. The hero of the book is [the city of] Baghdad: Jewish Baghdad and Muslim Baghdad and cosmopolitan Baghdad – its people, its belly dancers, its prime minister and the Jewish talmudic sage the Hacham Bashi, common people, Jews and Arabs, love stories. And, of course, the aliya of Iraqi Jews – the dream and its failure. It’s a book about a Baghdad that doesn’t exist anymore except in the memories of people who were there at that time. People were astonished to find out that I was barely 12 years old when I left Iraq. It is all the memories of a child.

How do you explain that?

Mainly because my memories were memories of emotions. The remembering was done through the revival of my feelings, my emotions. At some point, Israeli TV suggested that I go back to Iraq and they would shoot a film about me there. I asked the advice of a friend of mine in the Shin Bet. His answer was, “Eli, stay here and write books.” So the film was never made, but this book tells it all, down to the smell of the city I was born in, Baghdad. Shimon Peres told me that while reading it, he could feel himself wandering around in Baghdad’s narrow alleys. I told him, “Get rid of all these things you do and immerse yourself for a year – you will come out with your own Baghdad story.”

This region is not an easy one. How do you experience it as a writer who was born not far from here?

There is a sense of being a stranger to this region. We Israelis don’t really know it, its culture, its civilization. Our identity as a Western country and society is the worst thing for us. Whether we are right to be afraid or not, the fact is that we are surrounded by Muslims, first here inside the country and around us, by about one billion Muslims, so we do have a sense of being besieged. The only way to break through is by achieving peace. There is no other way.

And what about the status of Jerusalem?

Our minds still do not grasp it. We don’t understand that it is in our hands to change the reality around us. Jerusalem can be an open city. What do I care if there is an Arab flag on some building? What does it take away from me as a Jew living in this marvelous city? But first, we have to open ourselves to Arabic culture. The fact that Israeli youth do not know Arabic is a disaster in my eyes! We have to give up our Western way of looking at Oriental and Arabic culture because it is an arrogant look. But how can that happen? If the prime minister – any prime minister – doesn’t speak Arabic, why would our children bother to learn it?

As a writer, coming from there and living here, how would you describe the reality here?

We are living in a Masada state of mind. Our leadership is scaring us all the time. I don’t get it – we have the means to defend ourselves, we are not helpless. And although I do not look at the surrounding Arab world through rose-colored glasses, still we shouldn’t forget that we are no longer a helpless Jewish community in Eastern Europe.

The International Writers Festival is taking place in Jerusalem. What does Jerusalem mean to you?

Beauty. A city located among mountains cannot be less than beautiful: the natural landscape, the valleys around and the flowers – a real beauty. I am in love with Jerusalem. The Old City has tremendous charm. It is connected to history not only because of the heavy burden on our shoulders but also the architecture, the smells in the little narrow streets of the Old City, the colors. Yes, it has a historical deep insight – David and Jesus and Muhammad walked here. One doesn’t feel like an insignificant insect here – we are a link in a chain that goes back thousands of years, into the spiritual world of the three greatest faiths!

But a lot of people don’t want to live here. According to statistics, young people are leaving Jerusalem.

I think it is some kind of “bon ton.” There is no reason for that. Look at the exotic sights here, the extraordinarily wide variety of people here. I fell in love with Jerusalem at first sight, when I was only 16. And I have not wanted to be anywhere else since. I was living in the Katamonim; I was poor, but I managed to bring my parents here, and I was not ready to give in. And I haven’t moved from here since.

I do agree that Jerusalem was once a more intimate place to live. I loved it when it was a small, calm and much more modest city – before the huge tons of concrete that came after the Six Day War covered it. I wander a lot in the old neighborhoods – Mea She’arim, Nahlaot, the Christian monasteries, and you can still find those reminiscences in quite a few of these areas.November 11, 2010

By PEGGY CIDOR 04/30/2010 19:40 On the eve of the Second International Writers Festival, Eli Amir looks forward to discovering other authors’ secrets The International Writers Festival of Jerusalem is taking place this week at Mishkenot Sha’ananim. It will also be celebrating the 150th anniversary of the decision of Jewish families to leave the overcrowded […]

قراءة المزيد

Posted on

Posted on

Los Angeles Times 4/11/2010

When talking about life in the old country, Israel's Iraqi-born Jews acknowledge two eras: before the Farhoud, and after. In June 1941, during the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, nearly 200 of Baghdad's Jews were slain in a killing rampage that went on for several days. Things were never the same after the pogrom that marked the beginning of the end of the Jewish community that had lived in Iraq since antiquity. Most of Iraq's Jews -- about 150,000 -- left for Israel within a few years of the massacre.

Around 6,000 remained of the community that had lived in Iraq for more than 2,000 years.

In 1969, dwindled Iraqi Jewry suffered another shock, when nine men from Baghdad and Basra were rounded up and accused of spying for Israel. The trial concluded quickly and their inevitable execution was a public event that crowds were encouraged to witness and cheer. The Baghdad hangings followed closely on the heels of the Baath coup of 1968; Saddam Hussein was President Ahmed Hassan Bakr's right-hand man.

That day, the Israeli parliament stood silently in their memory. Prime Minister Levi Eshkol said that they had approached heads of state, religious authorities and even the United Nations secretary-general to intervene with the Iraqi rulers to reverse the sentence but to no avail. The charges were false, the trial a charade and the nine were killed just for being Jews, he said.

In a memorial ceremony this January, Salima Gabbay, whose husband, Fouad, was among those hanged, expressed the hope that their remains could one day be brought to Israel for burial.

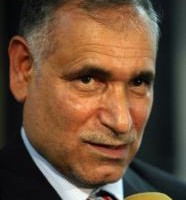

Last week, a monument was dedicated to the victims of both incidents. A 16-foot bronze sculpture titled "The Prayer" by artist Yasha Shapira was placed in the town of Ramat Gan, home to a large community of Iraqi Jews. The dedication was attended by Binyamin Ben-Eliezer, minister of industry, trade and labor.

Ben-Eliezer made the treacherous journey from Iraq to Israel in his boyhood; he has old photographs of his native Basra on his office walls. He said he was moved by the ceremony and sculpture that paid tribute to the cruelest incidents the Jewish community of Iraq had suffered and stressed more than anything the need for a Jewish homeland. He thanked the mayor and artist as government minister but also as a son of the community for the "commemoration of Iraqi Jews killed only for belonging to the Jewish people."

And he drew a line from then to now too. "On the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day, I say loud and clear to those threatening to destroy us.... Our state is not a miracle but proof that the Jewish nation will live on and successfully confront the challenges it faces." Holocaust Remembrance Day is being marked in Israel on Monday.

-- Batsheva Sobelman in Jerusalem

Above: Industry Minister Binyamin Ben-Eliezer, left, sculptor Yasha Shapira and Ramat Gan Mayor Zvi Bar. Courtesy of Ben-Eliezer's office.November 11, 2010

Los Angeles Times 4/11/2010 When talking about life in the old country, Israel’s Iraqi-born Jews acknowledge two eras: before the Farhoud, and after. In June 1941, during the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, nearly 200 of Baghdad’s Jews were slain in a killing rampage that went on for several days. Things were never the same after […]

قراءة المزيد

Posted on Point of no return

02/25/2011

By Mazan Latif for As-Sabaah Iraqi daily newspaper

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="368" caption="Jews at Tomb of Ezekiel in the 1930's"] [/caption]

Lately, a lot has been said about the shrine of Kefel or what is called by the Jews 'the shrine of the Prophet Ezekiel.'

The shrine is of great importance to all Jews, but in particular to the Jews of Iraq to whom ownership was given by the Ottoman Sultan Abdel Hamid.

The Jews used to visit the site yearly to pray and hold big celebrations. They used to slaughter and distribute the meat to the poor. The men in charge and the rabbis used to pray daily there until the mass exodus of the Jews from Iraq in 1951.

The village of Kefel is situated about 20 miles south of the town Hilla. In the Kefel is buried the Prophet Ezekiel z"l. The prophet Ezekiel is said to be a Cohen (descendant of the High Priest) from Jerusalem. Another seven Cohanim are buried there.

According to the Jews, the Prophet Ezekiel is mentioned in the Torah. The tomb of Ezekiel used to be covered with an expensive carpet and a hand-embroidered cloth. King Yehoyachin built a fence around the tomb with the help of many Jews.

The Jews bought the land near the shrine where they built a market and houses to be used by the Jewish guardians of the shrine and by the Rabbis in charge.

In 1860, the Muslims claimed the shrine and all the buildings around it for themselves. With the help of the Daniel family and and after many inquiries to Istanbul, the Ottoman authorities decided that the shrine belonged to the Jews and that the minaret did not belong to a mosque as the Muslims claimed.

The Muslim story claimed that the Prophet is an Arabic prophet descended from the Prophet Isma'el (Yishma'el). They lost their claim.

The Muslims from Hilla visit and pray in Kefel as they believe that the Prophet is a great one and mentioned in the Koran.

The minaret of the shrine is in a very bad condition and is supported by wooden poles to prevent it from falling.

The Jews used to own large libraries in their homes. When an owner died, all his books went to the Kefel library. After the mass exodus in 1951, all the books were kept in wooden boxes and covered with bricks. In the Seventies, someone destroyed all the boxes and the Hebrew books were scattered in the streets. As for the marble tablets that decorated the walls with the Hebrew inscriptions, they were stolen and sold to collectors who are interested in Jewish art.

Lately, after my visit in 2010 to the site, unfortunately what I saw was heartbreaking. Most of the Hebrew writings on the walls were erased. The tomb of Daniel was also in bad condition as well as the tombs of members of his family.

I did not see anything indicating that the site had a mosque or any sign of a Muslim site.

Unfortunately the Jewish shrine is in a very bad shape. Also there was no sign of the Sefer Torah the Jews used to pray with.

I am writing what my conscience dictates. I pray for a free Iraq true to its motto (Religion for God and the Homeland for all).

I ask the President of Iraq, the government, and all the people in charge to look after and preserve Iraq's true heritage.

Mazin Latif is an active Baghdadi journalist and writer specialising in Iraqi Jewish affairs. The article was summarised by Mrs. Eileen Khalastchy of London from an article in the As-Sabaah Iraqi daily newspaper ( Iraqi Information Net 13 February, 2011) http://www.alsabaah.com

View article hereJune 14, 2011

[/caption]

Lately, a lot has been said about the shrine of Kefel or what is called by the Jews 'the shrine of the Prophet Ezekiel.'

The shrine is of great importance to all Jews, but in particular to the Jews of Iraq to whom ownership was given by the Ottoman Sultan Abdel Hamid.

The Jews used to visit the site yearly to pray and hold big celebrations. They used to slaughter and distribute the meat to the poor. The men in charge and the rabbis used to pray daily there until the mass exodus of the Jews from Iraq in 1951.

The village of Kefel is situated about 20 miles south of the town Hilla. In the Kefel is buried the Prophet Ezekiel z"l. The prophet Ezekiel is said to be a Cohen (descendant of the High Priest) from Jerusalem. Another seven Cohanim are buried there.

According to the Jews, the Prophet Ezekiel is mentioned in the Torah. The tomb of Ezekiel used to be covered with an expensive carpet and a hand-embroidered cloth. King Yehoyachin built a fence around the tomb with the help of many Jews.

The Jews bought the land near the shrine where they built a market and houses to be used by the Jewish guardians of the shrine and by the Rabbis in charge.

In 1860, the Muslims claimed the shrine and all the buildings around it for themselves. With the help of the Daniel family and and after many inquiries to Istanbul, the Ottoman authorities decided that the shrine belonged to the Jews and that the minaret did not belong to a mosque as the Muslims claimed.

The Muslim story claimed that the Prophet is an Arabic prophet descended from the Prophet Isma'el (Yishma'el). They lost their claim.

The Muslims from Hilla visit and pray in Kefel as they believe that the Prophet is a great one and mentioned in the Koran.

The minaret of the shrine is in a very bad condition and is supported by wooden poles to prevent it from falling.

The Jews used to own large libraries in their homes. When an owner died, all his books went to the Kefel library. After the mass exodus in 1951, all the books were kept in wooden boxes and covered with bricks. In the Seventies, someone destroyed all the boxes and the Hebrew books were scattered in the streets. As for the marble tablets that decorated the walls with the Hebrew inscriptions, they were stolen and sold to collectors who are interested in Jewish art.

Lately, after my visit in 2010 to the site, unfortunately what I saw was heartbreaking. Most of the Hebrew writings on the walls were erased. The tomb of Daniel was also in bad condition as well as the tombs of members of his family.

I did not see anything indicating that the site had a mosque or any sign of a Muslim site.

Unfortunately the Jewish shrine is in a very bad shape. Also there was no sign of the Sefer Torah the Jews used to pray with.

I am writing what my conscience dictates. I pray for a free Iraq true to its motto (Religion for God and the Homeland for all).

I ask the President of Iraq, the government, and all the people in charge to look after and preserve Iraq's true heritage.

Mazin Latif is an active Baghdadi journalist and writer specialising in Iraqi Jewish affairs. The article was summarised by Mrs. Eileen Khalastchy of London from an article in the As-Sabaah Iraqi daily newspaper ( Iraqi Information Net 13 February, 2011) http://www.alsabaah.com

View article hereJune 14, 2011

Lately, a lot has been said about the shrine of Kefel or what is called by the Jews ‘the shrine of the Prophet Ezekiel.’

The shrine is of great importance to all Jews, but in particular to the Jews of Iraq to whom ownership was given by the Ottoman Sultan Abdel Hamid.

The Jews used to visit the site yearly to pray and hold big celebrations. They used to slaughter and distribute the meat to the poor. The men in charge and the rabbis used to pray daily there until the mass exodus of the Jews from Iraq in 1951.

قراءة المزيد

May 13, 2010

May 13, 2010

[/caption]

Lately, a lot has been said about the shrine of Kefel or what is called by the Jews 'the shrine of the Prophet Ezekiel.'

The shrine is of great importance to all Jews, but in particular to the Jews of Iraq to whom ownership was given by the Ottoman Sultan Abdel Hamid.

The Jews used to visit the site yearly to pray and hold big celebrations. They used to slaughter and distribute the meat to the poor. The men in charge and the rabbis used to pray daily there until the mass exodus of the Jews from Iraq in 1951.

The village of Kefel is situated about 20 miles south of the town Hilla. In the Kefel is buried the Prophet Ezekiel z"l. The prophet Ezekiel is said to be a Cohen (descendant of the High Priest) from Jerusalem. Another seven Cohanim are buried there.

According to the Jews, the Prophet Ezekiel is mentioned in the Torah. The tomb of Ezekiel used to be covered with an expensive carpet and a hand-embroidered cloth. King Yehoyachin built a fence around the tomb with the help of many Jews.

The Jews bought the land near the shrine where they built a market and houses to be used by the Jewish guardians of the shrine and by the Rabbis in charge.

In 1860, the Muslims claimed the shrine and all the buildings around it for themselves. With the help of the Daniel family and and after many inquiries to Istanbul, the Ottoman authorities decided that the shrine belonged to the Jews and that the minaret did not belong to a mosque as the Muslims claimed.

The Muslim story claimed that the Prophet is an Arabic prophet descended from the Prophet Isma'el (Yishma'el). They lost their claim.

The Muslims from Hilla visit and pray in Kefel as they believe that the Prophet is a great one and mentioned in the Koran.

The minaret of the shrine is in a very bad condition and is supported by wooden poles to prevent it from falling.

The Jews used to own large libraries in their homes. When an owner died, all his books went to the Kefel library. After the mass exodus in 1951, all the books were kept in wooden boxes and covered with bricks. In the Seventies, someone destroyed all the boxes and the Hebrew books were scattered in the streets. As for the marble tablets that decorated the walls with the Hebrew inscriptions, they were stolen and sold to collectors who are interested in Jewish art.

Lately, after my visit in 2010 to the site, unfortunately what I saw was heartbreaking. Most of the Hebrew writings on the walls were erased. The tomb of Daniel was also in bad condition as well as the tombs of members of his family.

I did not see anything indicating that the site had a mosque or any sign of a Muslim site.

Unfortunately the Jewish shrine is in a very bad shape. Also there was no sign of the Sefer Torah the Jews used to pray with.

I am writing what my conscience dictates. I pray for a free Iraq true to its motto (Religion for God and the Homeland for all).

I ask the President of Iraq, the government, and all the people in charge to look after and preserve Iraq's true heritage.

Mazin Latif is an active Baghdadi journalist and writer specialising in Iraqi Jewish affairs. The article was summarised by Mrs. Eileen Khalastchy of London from an article in the As-Sabaah Iraqi daily newspaper ( Iraqi Information Net 13 February, 2011) http://www.alsabaah.com

View article hereJune 14, 2011

لا تعليقات

[/caption]

Lately, a lot has been said about the shrine of Kefel or what is called by the Jews 'the shrine of the Prophet Ezekiel.'

The shrine is of great importance to all Jews, but in particular to the Jews of Iraq to whom ownership was given by the Ottoman Sultan Abdel Hamid.

The Jews used to visit the site yearly to pray and hold big celebrations. They used to slaughter and distribute the meat to the poor. The men in charge and the rabbis used to pray daily there until the mass exodus of the Jews from Iraq in 1951.

The village of Kefel is situated about 20 miles south of the town Hilla. In the Kefel is buried the Prophet Ezekiel z"l. The prophet Ezekiel is said to be a Cohen (descendant of the High Priest) from Jerusalem. Another seven Cohanim are buried there.

According to the Jews, the Prophet Ezekiel is mentioned in the Torah. The tomb of Ezekiel used to be covered with an expensive carpet and a hand-embroidered cloth. King Yehoyachin built a fence around the tomb with the help of many Jews.

The Jews bought the land near the shrine where they built a market and houses to be used by the Jewish guardians of the shrine and by the Rabbis in charge.

In 1860, the Muslims claimed the shrine and all the buildings around it for themselves. With the help of the Daniel family and and after many inquiries to Istanbul, the Ottoman authorities decided that the shrine belonged to the Jews and that the minaret did not belong to a mosque as the Muslims claimed.

The Muslim story claimed that the Prophet is an Arabic prophet descended from the Prophet Isma'el (Yishma'el). They lost their claim.

The Muslims from Hilla visit and pray in Kefel as they believe that the Prophet is a great one and mentioned in the Koran.

The minaret of the shrine is in a very bad condition and is supported by wooden poles to prevent it from falling.

The Jews used to own large libraries in their homes. When an owner died, all his books went to the Kefel library. After the mass exodus in 1951, all the books were kept in wooden boxes and covered with bricks. In the Seventies, someone destroyed all the boxes and the Hebrew books were scattered in the streets. As for the marble tablets that decorated the walls with the Hebrew inscriptions, they were stolen and sold to collectors who are interested in Jewish art.

Lately, after my visit in 2010 to the site, unfortunately what I saw was heartbreaking. Most of the Hebrew writings on the walls were erased. The tomb of Daniel was also in bad condition as well as the tombs of members of his family.

I did not see anything indicating that the site had a mosque or any sign of a Muslim site.

Unfortunately the Jewish shrine is in a very bad shape. Also there was no sign of the Sefer Torah the Jews used to pray with.

I am writing what my conscience dictates. I pray for a free Iraq true to its motto (Religion for God and the Homeland for all).

I ask the President of Iraq, the government, and all the people in charge to look after and preserve Iraq's true heritage.

Mazin Latif is an active Baghdadi journalist and writer specialising in Iraqi Jewish affairs. The article was summarised by Mrs. Eileen Khalastchy of London from an article in the As-Sabaah Iraqi daily newspaper ( Iraqi Information Net 13 February, 2011) http://www.alsabaah.com

View article hereJune 14, 2011

لا تعليقات