Karmel Melamed

“I will never forget when I first saw his body — they shot him with one bullet at point-blank range in his heart,” my father, George Melamed, shared with me a few weeks ago, reflecting on his friend — and brother-in-law’s brother — Ebrahim (Ebi) Berookhim, who was executed in an Iranian prison on July 31, 1980, at the age of 30. For the past 30 years, my father has rarely spoken of this young Jewish man’s killing and the circumstances that propelled our family’s abrupt flight from Iran. During these past three decades, he’s tried to forget how Ebi was unjustly accused of being an Israeli and American spy, then ruthlessly murdered by Iran’s radical Islamic regime.

Yet as Ebi’s 30th yahrzeit approached this month, my parents, our relatives and some local Iranian Jews who knew this successful young Jewish businessman finally opened up to me about this tragedy that completely transformed all of our lives.

With news of the Iranian government’s pursuit of nuclear weapons continually filling today’s airwaves, the story of Ebi’s killing serves as a stark reminder to us all of the continuing brutality and illogical nature of the ayatollahs’ regime in Iran. The Iranian government’s inhumane practice of random arrests and imprisonment of innocent individuals continues to this day: On July 31, 2009, the same date that Ebi died but 29 years later, three American hikers were randomly taken hostage in Iran for mistakenly crossing a border; they remain unfairly imprisoned. Last year, Roxana Saberi, an Iranian American journalist based in Tehran, was arrested on false charges of espionage — she was one of the lucky ones; after immense pressure from abroad, the Iranian authorities released her.

Ebi, my relative, wasn’t so lucky. And the pain of losing him continues to haunt our family three decades later. The person closest to Ebi during the final months of his life was his elder sister, Shaheen Makhani, who today is a businesswoman and grandmother living in Santa Monica. I met with her and her family earlier this month, and they wept silently as they told me their story, speaking publicly for the first time about Ebi and his tragic demise.

“He was four years younger than me. We were very close, and I loved him,” Shaheen told me. “He had just returned from America after getting his degree, and he had also completed his mandatory military service in the Iranian army. He had his whole future ahead of him.”

Shaheen said Ebi’s problems started with the beginning of Iran’s Islamic revolution, in early 1979, when the Berookhim family’s five-star Royal Gardens hotel in Tehran was confiscated by the newly formed Islamic regime of the Ayatollah Khomeini. Nearly all of his family had already fled Iran for the United States in the prior months, but Ebi remained behind. One day, armed thugs of the regime overran the hotel and quickly blindfolded him. They took him to the Khasr prison in Tehran on trumped-up charges of being an American and Israeli spy.

“We knew they had arrested and imprisoned Ebi in order to get at our family’s other assets, and therefore it was not easy to get him out of prison,” Shaheen said. “It was a nightmare because we didn’t know what they were going to do with Ebi.”

I recently discovered that while Ebi was in Khasr prison, he befriended other Jews who also were unjustly being held captive, including Behrooz Meimand, now a 64-year-old insurance salesman living in Los Angeles. Meimand told me recently that “until the last day we were in the Khasr prison, Ebi and I were together, and he often rested his head in my lap and wept — I felt as if he was like my younger brother, and I tried to comfort him during the difficult days.”

Ebi’s sister Shaheen said that two months after her brother was captured, she was finally able to get him released from prison, but only after paying what she said were ridiculously large bribes and other payments to the prison officials.

Each and every one of Ebi’s family members and friends whom I spoke with said they urged Ebi to escape from Iran after his release from prison, but he responded negatively to them all.

My father recalled one conversation he had with Ebi after a Shabbat dinner following Ebi’s release: “I told him to get the hell out of Iran because these people in the government had a case against him and wanted his family’s properties — but he responded, ‘No, no, no … my family and I are innocent. We didn’t do anything wrong or illegal. Why should I leave?’ ”

This mistake of remaining in Iran proved fatal for Ebi. But he didn’t see what was coming. Shaheen said that, in the months after Ebi’s first arrest, he and his 82-year-old father, Eshagh Berookhim, voluntarily visited the infamous Evin prison, located just north of Tehran, because they believed promises the Iranian officials had made to them — that their hotel would be returned when they agreed to present their case at the prison. Then, one morning, in April 1980, during one of these voluntary visits, the Evin prison authorities arrested Ebi again and sent him to prison. This time, his elderly father was arrested with him.

Over the next nearly four months, Shaheen worked tirelessly to free them. Then, early one morning, she turned on the radio and was devastated to learn that her beloved brother had been executed at the prison earlier that same day.

Around the same time, my father heard the news from a co-worker, and he, too, was shocked. Without hesitation, my father and three other Jews risked their lives by going to the prison morgue to retrieve Ebi’s body because most of his family was no longer in Iran to give him a kosher burial. Ebi’s father was still being held.

“It was dangerous at the time to get his body because the authorities would ask what relationship you have with the infidel who was executed or demand to see your identification. And they could create all sorts of future problems for you,” my father told me. “But I nevertheless went with a few others, because Ebi was a close friend of mine and a family member whom we could not allow to be buried in a mass grave with the other executed political prisoners.”

The regime’s prison officials refused to release Ebi’s body until a substantial payment was made to “cover the costs for the bullet used in the execution,” he said.

My father and the other Jewish men paid and were eventually given Ebi’s bloody body. My father recalled: “Ebi’s body was still warm while he lay in the mortuary at the Jewish cemetery; it had been desecrated with markers, and the soles of his feet showed signs that he had been tortured with steel wiring.” He also said, “You could tell he was shot at point-blank range, because the opening was a half an inch in diameter on the front of his body near his heart, and the hole on his back side was two or three inches wide.”

Shaheen, her husband, Masood, and other friends and family were at Ebi’s burial in Tehran’s Jewish cemetery. Several weeks later, Shaheen said she was able to bribe the prison officials by paying them a substantial amount of money to release her elderly father, who had been moved to the prison hospital due to his poor health. When he was released, Eshagh repeatedly asked for Ebi but was not told of his beloved son’s execution. Instead, Eshagh was hidden inside another family member’s home, then smugglers were paid to carry him on a camel across the border out of Iran and into Turkey. Shaheen said that, at the same time, she and her husband were fortunate enough to flee Iran on a flight to Germany. Only after the three were reunited in Germany were they able to mourn Ebi in peace. It was there that she finally broke the news of Ebi’s execution to her father.

My mother, Roset Melamed, recalled for me the immediate aftereffects that Ebi’s execution had on my own father, who had been Ebi’s close childhood friend.

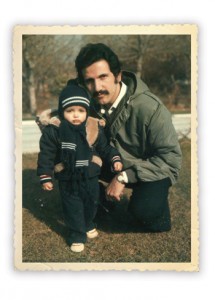

“When your father returned, after he had seen Ebi’s body and had been to the funeral, he was no longer the same happy and carefree man as before,” she told me. “It was as if something inside of him died. He did not want to listen to music anymore; he did not want to play with you, his young son, who was so sweet and starting to talk. He just stared at you for long periods of time, and it seemed as if life did not matter anymore to him.”

Another of Ebi’s older sisters, Negar Berookhim, told me that the entire Iranian Jewish community living in Los Angeles at the time was shocked and infuriated when they learned of Ebi’s execution. She said that nearly 1,000 members of the community flooded Sinai Temple in West Los Angeles for a memorial seven days after his killing.

Even though the Iranian government never officially announced its reasons for executing Ebi, his friends, family and other Iranian Jews living in Southern California have their own theories. Some believe he was executed to strike fear into the hearts of Jews in Iran, to force them to abandon their substantial assets so the government could confiscate them. Others believe the execution may have been an act of revenge by the Iranian clerics and Palestinian terrorists in Iran following Israel’s declaration of Jerusalem as its undivided and eternal capital not long before this time. A few individuals close to the Berookhim family also believe that some of their hotel’s former disgruntled employees who had become officials in the new regime may have conspired to have Ebi killed out of jealousy or in order to confiscate his family’s wealth.

My parents told me that Ebi’s execution was the final breaking point in their decision to flee Iran and leave behind all our assets; we left in September 1980. As it turned out, we were among the last to flee Iran via plane; Tehran’s international airport was shut down just three days after our flight because of the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War. We traveled first to Germany, where my father had relatives living in Hamburg, but we had not had time to obtain entry visas amid the chaos of our departure from Iran. Once again, we were immensely fortunate — the immigration agent granted my family visas at our arrival after my father spoke fluently to him in German and explained our predicament.

From Germany, we had a brief stay in Israel, and then, two months after leaving our Iranian home, we finally immigrated to Los Angeles, where my parents restarted their lives from zero.

Even so, my parents recently admitted to me that they probably would have remained in Iran to this day, to care for my elderly grandparents, had Ebi not been executed. And the ripples from his death went even further. Ebi’s execution caused another massive wave of Jews in Tehran and elsewhere in Iran to sell what assets they could at bargain prices and flee the country.

Ebi was officially only the third Jew to be executed by the Islamic government in Iran. Two other more prominent Jews were executed before him on similar false charges of espionage for Israel and the United States. The first was Habib Elghanian, the leader of Iran’s Jewish community, who was executed in May 1979. The second was the well-known Jewish businessman Albert Danielpour, who was executed in June 1980 in the city of Hamadan.

According to a 2004 report prepared by Frank Nikbakht, an Iranian Jewish activist who heads the Los Angeles-based Committee for Minority Rights in Iran, the Jewish community in Iran continues to live in constant fear for its security amid threats from Islamic terrorist factions. Since 1979, at least 14 Jews have been murdered or assassinated by the regime’s agents, at least two Jews have died while in custody, and 11 Jews have been officially executed by the regime. In 1999, Feizollah Mekhoubad, a 78-year-old cantor of the popular Yousefabad synagogue in Tehran, was the last Jew officially to be executed by the regime, according to the report.

In 2000, with the assistance of various American Jewish groups, the Iranian Jewish community in the United States, but particularly in Los Angeles, was able to publicize the case of 13 Iranian Jews from the city of Shiraz who had been imprisoned in 1999 on fabricated charges of spying for Israel. Ultimately, the international exposure put pressure on the Iranian regime, and the “Shiraz 13” eventually were released.

Despite the painful memories surrounding the execution of Ebi, our family members, like my relative Abraham Berookhim — Ebi’s nephew — said they do not harbor ill will toward Iranian Muslims in general.

“I don’t want people to think that all Muslims are bad, because it’s not true — some of my friends and even my business partner are Muslims and they’re great people,” Abraham told me. “We oppose the regime of Iran and their radical leadership.”

But the lasting effects of Ebi’s execution are still felt by my parents and the rest of our family. The emotional scars from 30 years ago have not fully healed for any of them. For the first time since Ebi’s execution, my father openly admitted that many nights he is still haunted by nightmares of the tragedy. “Even though I have nightmares of what happened to Ebi, I wanted to talk about how Ebi was killed,” my father said, “because I want others to know what an injustice happened to an innocent man.” And despite experiencing tremendous hardships and persecution at the hands of the radical Islamic regime in Iran, the Iranian Jewish community in Southern California continues to be active in seeking to help its 20,000 Jewish brethren who remain there.

And the American Iranian Jews won’t be silenced: In September 2006, a lawsuit was filed against former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami in a U.S. federal court by the families of 12 Iranian Jews arrested by the Iranian secret police while attempting to flee from southwestern Iran into Pakistan between 1994 and 1997; the 12 were never heard from again. The suit alleges Khatami authorized the arrest and indefinite imprisonment of those 12 Iranian Jews. While the regime never defended its case in court, the suit kept alive the story of the 12 missing Jews in the public eye and kept the spotlight on the Iranian regime’s human rights abuses.

After hearing their family’s stories of struggling and escaping from Iran, likewise many young professionals in the Iranian Jewish community, including the organization 30 Years After, continue to work hard to have their voices heard. It is stories like my cousin Ebi’s that refuse to die and that have brought a new generation of Iranian Jews to embrace political involvement in their homeland, the United States, when it comes to issues of Iran.

For more in-depth interviews related to this story, visit Karmel Melamed’s blog at jewishjournal.com/iranianamericanjews/.