Annie Liberman

Among the First Wave Leaving Tunisia

By Annie Liberman (née Fellous)

There were significant differences in the severity of the treatment suffered by Jews during their uprooting from North Africa and the Middle East. In Iraq the famous farhouds brought terror to a huge Jewish Community and in Egypt many were incarcerated for years with no knowledge of when and if they would be released. In Tunisia, however, Jews and Moslem Arabs maintained friendly relations, by and large, for a number of years following the independence of Tunisia in 1956.

“My father saw that the country was becoming Arab and the French influence, a thing of the past,” says Annie Liberman. “He sensed a schism and felt that we wouldn’t be regarded as citizens anymore. When he thought about the future he saw that life would be more difficult for us. We were not angry. We just thought that it was their country so let’s get out.” Annie’s father had obtained French citizenship when it was offered in 1923 and was working for the French government. He was able to secure a post in Paris and so the family packed up and left in 1958.

Many Jews stayed behind, including a number of Annie’s cousins, aunts and uncles who had not become French citizens. Despite promises by the government, their life as Tunisians did become progressively more difficult as the years passed. They suffered the effects of periodic anti-Jewish uprisings. Most ultimately emigrated to Israel and France. “The Jews who left in 1967 had it very hard. Jews were attacked in the streets, and the synagogue was burned. My cousins were forced to flee, leaving their homes and businesses behind.”

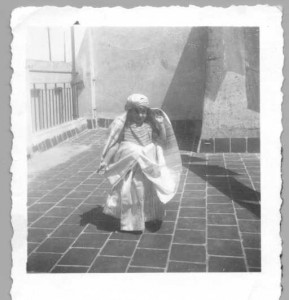

Annie Liberman was born Annie Esther Fellous in Tunis in early 1943, just months before the liberation of the city by the Allied Armies. Her older brother recounts the story of how he broke the curfew and dashed through darkened streets to notify the mid-wife, avoiding German soldiers along the way.

After the terrorization and persecution of the German occupation, the liberation brought a period of openness and safety to the Tunisian Jewish community. Annie learned Hebrew at the Jewish school in the synagogue and then French, her mother tongue, in public school.

Annie has fond memories of her first 15 years of life in Tunis, of a bustling and lively city with a vibrant Jewish community. “Life was simple,” she says. “Everybody got along quite nicely. When there was a Jewish celebration the Muslims and Christians would get involved and vice versa. We were celebrating the differences.” It is a joy when, by chance, she meets a Tunisian in the streets or in a market in the US. The conversations invariably turn to retelling of the good times and the sharing of good memories. The Arabic cultural sensibilities of her youth are still close to the surface. Along with recordings of a few French singers, her collection of CD’s has some Arabic music, though these songs all have Hebrew lyrics and are sung by Israeli singers.

Annie’s uncle on her father side, Emile Fellous, was the doctor of the Bey of Tunis, first the royal representative of the Ottoman occupiers of Tunisia and then the titular head of government under the French. Being the doctor of the Bey was a very prestigious position. He lived in a large Arabic style house in La Marsa, a picturesque village along the coast near Carthage, north of Tunis. As a child, Annie and her siblings would visit her uncle and the whole family would spend time at the nearby Saf-Saf café, sipping tea and watching the camel turn in a circle as he pulled water up from the well.

As the doctor of the Bey, her uncle was very well known and his reputation continued for many years beyond his own stay in the country. In 1969, Annie returned to Tunisia with her husband to show him the land in which she was raised. In Carthage, “when we arrived at the hotel we gave the concierge our passports. When he looked at mine he asked if I was the daughter of a doctor with the same name. I told him that I was his niece. He told us to sit and, when he returned, he brought champagne and Tunisian salads. ‘It is because of your uncle that I am alive,’ he said.”

The French occupation in the 19th century brought some protections to the Jewish Community. One of their first acts was to open up the Jewish Ghetto of La Hara in Tunis and offer Jews educational opportunities and legal rights. In return, the French expected the Jews to give their primary loyalty to France. However, many Tunisian Jews rejected the French offer, preferring to continue, effectively, to live under Moslem control as they had done for centuries. Annie’s grandmother’s name was Castro, a name traced back to the expulsion of Jews from Spain during the Inquisition. As a child she couldn’t understand that Arabic was the only language her grandmother ever spoke, and she remembers trying to teach her to count in French. Those who did become French nonetheless retained a strong Jewish identity and their role in the Jewish community by participating in the affairs of the religious institutions.

Annie Liberman explains that when Tunisia gained its independence on March 20 of 1956 it was natural for Tunisian Jews who had French citizenship to move to France. Because her father was in the French civil service, one of the family privileges had been long vacation trips to France every two years. She remembers the ship voyages across the Mediterranean and the long train rides to Paris. The family’s move to France after Tunisian independence was less traumatic than was the departure of many Jews from their homes in Arab lands.

Annie Liberman lived in Paris for eight years, finishing her education and immersing herself in the glamour and style of that exciting city. Eight years later she married an American and moved to Los Angeles. With its palm trees and mild climate, Los Angeles reminded her of Tunis. But neither the glimmer of Paris nor the rapid pace of Los Angeles could shake her Tunisian sensibilities. “It was very hot in Los Angeles and I wanted to take a nap but no one in America takes naps. In Tunisia there is no one in the streets from one to four o’clock. Then the cafes open and you can sit on the terrace and smell the jasmine and talk until midnight.”

Her husband of 38 years, an Ashkenazi born in America of Polish Russian immigrants, understands and appreciates the rhythm and vitality of Annie’s Mediterranean, Sephardic temperament. The only regret he registered, and a mild one at that, is that she has entirely eschewed cooking Tunisian foods and prepares Ashkenazi specialties exclusively for the holidays. While her chicken soup and matzoh balls are legendary in her family, they all still await, with great anticipation, her first Tunisian couscous. Remembering the hours and hours that her mother spent in the kitchen, Annie says they will have to wait a long, long time. “The thought of making a couscous gives me rasra (the Arabic word for anxiety)”

Annie Liberman’s life is firmly established in the United States. She and her husband now reside in California, and their three daughters as well . She looks forward to visiting Tunisia again, and especially showing her daughters the sights and places of her youth. A number of her brothers and cousins have visited recently, and tell of a pleasant and ostensibly tolerant Tunisia. She will return herself when the situation between Jews and Arabs stabilizes.