Posted on J Weekly of Northern California

September 15, 2011

By Dan Pine

Bay Area Jews from Egypt, Libya and Tunisia worry about their former Arab homelands

As Tahrir Square filled with hundreds of thousands of Egyptians, all demanding liberty, equality and fraternity, the world looked on in amazement. The so-called Arab Spring, which began last December, had by February fully blossomed in Cairo.

Also watching intensely from his Palo Alto home was Albert Bivas. The retired physicist knew Tahrir Square well. As a boy, he attended a school not far from it.

Bivas, 70, is an Egyptian Jew, raised in cultured elegance at a time when Cairo was a cosmopolitan world city. He spoke French as his first language and lived in Zamalek, a wealthy neighborhood located on an island in the Nile.

But Bivas’ idyllic upper-class life came to a halt in 1956 when he and his family, like many other Egyptian Jews, fled after the rise of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, a fierce Egyptian nationalist and staunch enemy of Israel. The Bivas family moved to France to start a new life.

Decades later, Albert Bivas watched his former countrymen peacefully overthrow the oppressive regime of President Hosni Mubarak. He couldn’t help but feel joy.

“I was supporting the people,” Bivas said in his distinctively French accent. “I hoped that the people wake up, take their lives in their hands and get rid of those who did not allow them to grow, to earn money, to have decent lives.”

He also frets over the outcome. Will the Egyptian people establish a democratic state, or would radicals take advantage of the disorder? And what will be the new Egyptian policy toward Israel and the Jews?

These questions plague not only pundits and international policymakers, but also Jews from Muslim countries witnessing the foment of the Arab Spring. Bay Area Jews born in those lands watch, wait and worry about their home countries.

With the chaos and near-tragedy of the Egyptian mob attacking the Israeli Embassy in Cairo on Sept. 9, and the subsequent reestablishment of martial law, those concerns grew more intense.

“[Egyptians] don’t have the know-how,” Bivas said. “I’m afraid the only groups organized enough are Islamist groups, groups we would call terrorists, with no respect for life. In the name of ideology, they may hijack the wonder of becoming free. People will have fought to become free and end up giving their freedom away.”

Bill Moran, a Livermore physicist, was glued to the television following the news from Egypt earlier this year. Born Nabil Mourad, he was raised in Halwan, a Cairo suburb so bereft of Jews, Moran’s parents didn’t tell their son he was Jewish until he had reached his teens.

Before they did, he said, “I learned to hate Jews and how bad the Jews are. Eventually I found out. It was a big shock. My parents did this to protect me and not be ostracized.”

Life for Jews in Egypt grew far more precarious after the 1967 Six-Day War, during which the Egyptian military suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of Israel. Two years later, at age 17, Moran left his country, exiled at the urging of his own parents, who stayed behind.

He joined a sister, who had previously immigrated to San Francisco. Moran also received help from Jewish Family and Children’s Services. Eventually he graduated from U.C. Berkeley and became a physicist at the Lawrence Livermore Labs. He built a new life in California, though traces of the old fear remained.

“I was afraid of saying I was Jewish for a long time, even though there was no anti-Semitism here,” Moran remembered. “I was just so cautious. Eventually I learned to trust people.”

Moran made a return visit to Egypt nine years ago. He saw for himself the corruption and social decay under Mubarak. That’s why he rejoiced at the sight of mass demonstrations — at least at first.

“One begins to wonder, will the Muslim Brotherhood take over,” he asked. “Will [Egypt] become a fanatic state? What about peace with Israel? I have no crystal ball, but my gut feeling is Egyptians in general are a bit more civilized than Iraqis, Syrians and Libyans. There are a lot of really good Egyptians. Most are just misinformed about the Jews, and they don’t know any Jews.”

Though he doesn’t expect war to break out between Egypt and Israel, as it had four times since the founding of the Jewish state, he is not surprised that Egypt’s border with Israel and Gaza has already become a flashpoint.

“It’s hard to know if they will have a real democracy with moderate leaders,” he added. “The majority of the population is not as fanatic as those [Islamist] groups. But instability can happen. I hope people will recognize the benefits of peace.”

The sustained, relative non-violence of this spring’s Egyptian revolution, despite the government’s brutal response, inspired the world.

That Egyptian revolt came after a peaceful revolt in Tunisia.

Marilyn Uzan of Palo Alto followed news reports during the Arab Spring. She focused on her homeland of Tunisia, the North African country where the revolutions began last December.

Like the uprisings in Egypt, Syria, Yemen and Libya, the Tunisian revolt brought great masses of people into the streets, clamoring for an end to the corrupt rule of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

Uzan, 43, watched as her former countrymen endured a harsh police response yet never lost their poise. By mid-January, Ben Ali and his family had fled to Saudi Arabia. The Tunisian people claimed victory.

“I was extremely proud to see that the people did their own fight,” Uzan said. “It was from their heart. They realized things were unfair. It was a beautiful movement, with very little violence.”

That peaceful approach meshed with Uzan’s sense of her country. She remembers Tunisia, and her hometown of Tunis, as relatively tolerant and progressive, especially for an Arab country.

Her family had lived there for generations, and though Jews did suffer second-class status, Uzan spent her first 17 years in Tunisia free from fear. Her favorite memory: playing on the Mediterranean beaches just north of the city.

“I am very happy about my upbringing there,” she said. “It was a very easy life. It sounds surprising, because so many talk about being mistreated in Arab countries. I experienced almost no racism personally. Everyone knew we were Jews. We did not hide it, we did not feel unsafe or insecure.”

A native French speaker, Uzan left Tunisia for France in 1985 before graduating high school. This was around the time Israel attacked PLO headquarters in Tunis. This led to a time of further uncertainty for Tunisian Jews, a community already in decline.

Uzan lived in France and, briefly, in England, for the next 15 years until, as she put it, “I was imported by my husband,” a Jewish American who brought his new bride to California.

Just as Bivas worries whether Egyptians will navigate the tricky political waters toward democracy, Uzan also wonders whether Tunisia can successful manage the same voyage.

At first, she said, “I thought, ‘My God, that tiny country did so much for the Arab world.’ Then I was very scared and worried. Are they going to make it? It’s not easy to become a democracy. They will need to know how to be independent, have [political] parties, create a new constitution: It’s not something you do overnight.”

Tunisia might have a head start. As a child, Uzan grew up under the rule of the late Tunisian president Habib Bourguiba, a leader sometimes compared to Mustafa Ataturk of Turkey. When he came to power in the mid-1950s, he ushered in reforms such as women’s emancipation, public education and healthcare.

He also protected Tunisia’s Jewish community from the worst abuses seen in other Arab countries. His successor, Ben Ali, evolved into a corrupt leader, condemned by leading human rights organizations for his authoritarian rule.

Ben Ali’s time ran out once the Tunisian people began mass protests last year. He found safety in exile. Not as lucky, Egypt’s Mubarak, now under house arrest and on trial.

The Egyptian and Tunisian revolts surprised the world with their minimal bloodshed. That’s not how things went down in neighboring Libya, which for months has been convulsed in a bloody civil war between supporters and opponents of Libyan dictator Muammar Gadhafi.

For Bay Area Jews of Libyan extraction, such as Dalia Sirkin, the battle there has been anything but inspiring.

“It pains me to see that, in order to have democracy and freedom, bloodshed is the cost,” said Sirkin, 61, a professor of English Composition at San Jose State University. “I really wish them well. I want any country to have the freedom to vote, to travel abroad, to own property. I hope [Libyans] have the freedoms that they denied us.”

By “us,” she means the Libyan Jews, who lived as an oppressed community for centuries and ultimately fled under fire in the wake of the Six-Day War.

Born Dalia Bokhobza in Tripoli, Sirkin grew up speaking Italian as her first language, though she also knew some Arabic and Hebrew. She remembers her home country as a beautiful place. To look at.

“We had the sea and the sand,” she said. “The Italian architecture, the sun, the gardens, the date palms. My memories are rich with beauty.”

Then there was the dark side of life, Sirkin says. “I don’t remember ever living without fear. There was no such thing as walking down the street and not worrying about being physically harassed.”

Unlike the comparatively mild Tunisia, Libya was a hotbed of anti-Jewish hatred. Sirkin lost a childhood friend to anti-Jewish violence. Murders occurred often and went unpunished.

“I don’t remember a single holiday where the Jews going to the synagogues were not harassed,” she went on. “[Muslims} would throw stones. Many synagogues were burned.”

Sirkin’s parents had their assets confiscated. By the time a then-17-year-old Sirkin, her parents and grandparents fled Libya in 1967 — with only one suitcase permitted per person — they knew their centuries-old presence in that country had come to an end.

Her parents and grandparents had a difficult time adjusting to a new life in exile in Rome. But Sirkin thrived. She lived in Rome for 11 years, and spent time studying English literature at Oxford University. She also lived in Israel for a few years, meeting her husband-to-be there.

The couple moved to San Francisco in 1981. They had three daughters, and later divorced.

Watching the Libyan civil war unfold over the last few months, Sirkin was not surprised her home country went down a more violent path than Egypt or Tunisia.

“We also were dealing with a dictator who was not willing to let go,” she said of Gadhafi. “Mubarak to some extent was trying to reach out with a little bit of dialogue. Gadhafi was determined to hold on to his power at all costs.”

Despite the international hope engendered by the Arab revolts, Sirkin counts herself among the pessimists, at least as far as Libya is concerned.

“I don’t know what has changed for the people,” she said. “I don’t think they are more benevolent towards Jews today than they were in 1967, because nothing changed in terms of who they are. We were not malevolent then and they still kicked us out.”

Bivas and Moran belong to JIMENA (Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa), a Bay Area organization that works on behalf of the nearly 1 million Jews exiled from Arab lands. The two are part of the JIMENA speakers’ bureau, sharing their stories.

With the tumultuous changes sweeping the Middle East, local Jews born in Arab lands realize the story isn’t over.

“The best we in the United States could do is let things happen,” Bivas said. “Let their ideas flourish, let them take responsibility for themselves.”

Speaking of her native Tunisia, Uzan could be speaking of any Arab country undergoing transition.

“We need to wait and see,” she said. “The Islamist movements have been somewhat contained in the past. From what I heard the Jews in Tunis are feeling a little insecure right now, and that’s sad.”

Read article here

October 24, 2011

Bay Area Jews from Egypt, Libya and Tunisia worry about their former Arab homelands

As Tahrir Square filled with hundreds of thousands of Egyptians, all demanding liberty, equality and fraternity, the world looked on in amazement. The so-called Arab Spring, which began last December, had by February fully blossomed in Cairo.

Also watching intensely from his Palo Alto home was Albert Bivas. The retired physicist knew Tahrir Square well. As a boy, he attended a school not far from it.

Bivas, 70, is an Egyptian Jew, raised in cultured elegance at a time when Cairo was a cosmopolitan world city. He spoke French as his first language and lived in Zamalek, a wealthy neighborhood located on an island in the Nile.

But Bivas’ idyllic upper-class life came to a halt in 1956 when he and his family, like many other Egyptian Jews, fled after the rise of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, a fierce Egyptian nationalist and staunch enemy of Israel. The Bivas family moved to France to start a new life.

Decades later, Albert Bivas watched his former countrymen peacefully overthrow the oppressive regime of President Hosni Mubarak. He couldn’t help but feel joy.

“I was supporting the people,” Bivas said in his distinctively French accent. “I hoped that the people wake up, take their lives in their hands and get rid of those who did not allow them to grow, to earn money, to have decent lives.”

He also frets over the outcome. Will the Egyptian people establish a democratic state, or would radicals take advantage of the disorder? And what will be the new Egyptian policy toward Israel and the Jews?

These questions plague not only pundits and international policymakers, but also Jews from Muslim countries witnessing the foment of the Arab Spring. Bay Area Jews born in those lands watch, wait and worry about their home countries.

With the chaos and near-tragedy of the Egyptian mob attacking the Israeli Embassy in Cairo on Sept. 9, and the subsequent reestablishment of martial law, those concerns grew more intense.

“[Egyptians] don’t have the know-how,” Bivas said. “I’m afraid the only groups organized enough are Islamist groups, groups we would call terrorists, with no respect for life. In the name of ideology, they may hijack the wonder of becoming free. People will have fought to become free and end up giving their freedom away.”

Bill Moran, a Livermore physicist, was glued to the television following the news from Egypt earlier this year. Born Nabil Mourad, he was raised in Halwan, a Cairo suburb so bereft of Jews, Moran’s parents didn’t tell their son he was Jewish until he had reached his teens.

Before they did, he said, “I learned to hate Jews and how bad the Jews are. Eventually I found out. It was a big shock. My parents did this to protect me and not be ostracized.”

Life for Jews in Egypt grew far more precarious after the 1967 Six-Day War, during which the Egyptian military suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of Israel. Two years later, at age 17, Moran left his country, exiled at the urging of his own parents, who stayed behind.

He joined a sister, who had previously immigrated to San Francisco. Moran also received help from Jewish Family and Children’s Services. Eventually he graduated from U.C. Berkeley and became a physicist at the Lawrence Livermore Labs. He built a new life in California, though traces of the old fear remained.

“I was afraid of saying I was Jewish for a long time, even though there was no anti-Semitism here,” Moran remembered. “I was just so cautious. Eventually I learned to trust people.”

Moran made a return visit to Egypt nine years ago. He saw for himself the corruption and social decay under Mubarak. That’s why he rejoiced at the sight of mass demonstrations — at least at first.

“One begins to wonder, will the Muslim Brotherhood take over,” he asked. “Will [Egypt] become a fanatic state? What about peace with Israel? I have no crystal ball, but my gut feeling is Egyptians in general are a bit more civilized than Iraqis, Syrians and Libyans. There are a lot of really good Egyptians. Most are just misinformed about the Jews, and they don’t know any Jews.”

Though he doesn’t expect war to break out between Egypt and Israel, as it had four times since the founding of the Jewish state, he is not surprised that Egypt’s border with Israel and Gaza has already become a flashpoint.

“It’s hard to know if they will have a real democracy with moderate leaders,” he added. “The majority of the population is not as fanatic as those [Islamist] groups. But instability can happen. I hope people will recognize the benefits of peace.”

The sustained, relative non-violence of this spring’s Egyptian revolution, despite the government’s brutal response, inspired the world.

That Egyptian revolt came after a peaceful revolt in Tunisia.

Marilyn Uzan of Palo Alto followed news reports during the Arab Spring. She focused on her homeland of Tunisia, the North African country where the revolutions began last December.

Like the uprisings in Egypt, Syria, Yemen and Libya, the Tunisian revolt brought great masses of people into the streets, clamoring for an end to the corrupt rule of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

Uzan, 43, watched as her former countrymen endured a harsh police response yet never lost their poise. By mid-January, Ben Ali and his family had fled to Saudi Arabia. The Tunisian people claimed victory.

“I was extremely proud to see that the people did their own fight,” Uzan said. “It was from their heart. They realized things were unfair. It was a beautiful movement, with very little violence.”

That peaceful approach meshed with Uzan’s sense of her country. She remembers Tunisia, and her hometown of Tunis, as relatively tolerant and progressive, especially for an Arab country.

Her family had lived there for generations, and though Jews did suffer second-class status, Uzan spent her first 17 years in Tunisia free from fear. Her favorite memory: playing on the Mediterranean beaches just north of the city.

“I am very happy about my upbringing there,” she said. “It was a very easy life. It sounds surprising, because so many talk about being mistreated in Arab countries. I experienced almost no racism personally. Everyone knew we were Jews. We did not hide it, we did not feel unsafe or insecure.”

A native French speaker, Uzan left Tunisia for France in 1985 before graduating high school. This was around the time Israel attacked PLO headquarters in Tunis. This led to a time of further uncertainty for Tunisian Jews, a community already in decline.

Uzan lived in France and, briefly, in England, for the next 15 years until, as she put it, “I was imported by my husband,” a Jewish American who brought his new bride to California.

Just as Bivas worries whether Egyptians will navigate the tricky political waters toward democracy, Uzan also wonders whether Tunisia can successful manage the same voyage.

At first, she said, “I thought, ‘My God, that tiny country did so much for the Arab world.’ Then I was very scared and worried. Are they going to make it? It’s not easy to become a democracy. They will need to know how to be independent, have [political] parties, create a new constitution: It’s not something you do overnight.”

Tunisia might have a head start. As a child, Uzan grew up under the rule of the late Tunisian president Habib Bourguiba, a leader sometimes compared to Mustafa Ataturk of Turkey. When he came to power in the mid-1950s, he ushered in reforms such as women’s emancipation, public education and healthcare.

He also protected Tunisia’s Jewish community from the worst abuses seen in other Arab countries. His successor, Ben Ali, evolved into a corrupt leader, condemned by leading human rights organizations for his authoritarian rule.

Ben Ali’s time ran out once the Tunisian people began mass protests last year. He found safety in exile. Not as lucky, Egypt’s Mubarak, now under house arrest and on trial.

The Egyptian and Tunisian revolts surprised the world with their minimal bloodshed. That’s not how things went down in neighboring Libya, which for months has been convulsed in a bloody civil war between supporters and opponents of Libyan dictator Muammar Gadhafi.

For Bay Area Jews of Libyan extraction, such as Dalia Sirkin, the battle there has been anything but inspiring.

“It pains me to see that, in order to have democracy and freedom, bloodshed is the cost,” said Sirkin, 61, a professor of English Composition at San Jose State University. “I really wish them well. I want any country to have the freedom to vote, to travel abroad, to own property. I hope [Libyans] have the freedoms that they denied us.”

By “us,” she means the Libyan Jews, who lived as an oppressed community for centuries and ultimately fled under fire in the wake of the Six-Day War.

Born Dalia Bokhobza in Tripoli, Sirkin grew up speaking Italian as her first language, though she also knew some Arabic and Hebrew. She remembers her home country as a beautiful place. To look at.

“We had the sea and the sand,” she said. “The Italian architecture, the sun, the gardens, the date palms. My memories are rich with beauty.”

Then there was the dark side of life, Sirkin says. “I don’t remember ever living without fear. There was no such thing as walking down the street and not worrying about being physically harassed.”

Unlike the comparatively mild Tunisia, Libya was a hotbed of anti-Jewish hatred. Sirkin lost a childhood friend to anti-Jewish violence. Murders occurred often and went unpunished.

“I don’t remember a single holiday where the Jews going to the synagogues were not harassed,” she went on. “[Muslims} would throw stones. Many synagogues were burned.”

Sirkin’s parents had their assets confiscated. By the time a then-17-year-old Sirkin, her parents and grandparents fled Libya in 1967 — with only one suitcase permitted per person — they knew their centuries-old presence in that country had come to an end.

Her parents and grandparents had a difficult time adjusting to a new life in exile in Rome. But Sirkin thrived. She lived in Rome for 11 years, and spent time studying English literature at Oxford University. She also lived in Israel for a few years, meeting her husband-to-be there.

The couple moved to San Francisco in 1981. They had three daughters, and later divorced.

Watching the Libyan civil war unfold over the last few months, Sirkin was not surprised her home country went down a more violent path than Egypt or Tunisia.

“We also were dealing with a dictator who was not willing to let go,” she said of Gadhafi. “Mubarak to some extent was trying to reach out with a little bit of dialogue. Gadhafi was determined to hold on to his power at all costs.”

Despite the international hope engendered by the Arab revolts, Sirkin counts herself among the pessimists, at least as far as Libya is concerned.

“I don’t know what has changed for the people,” she said. “I don’t think they are more benevolent towards Jews today than they were in 1967, because nothing changed in terms of who they are. We were not malevolent then and they still kicked us out.”

Bivas and Moran belong to JIMENA (Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa), a Bay Area organization that works on behalf of the nearly 1 million Jews exiled from Arab lands. The two are part of the JIMENA speakers’ bureau, sharing their stories.

With the tumultuous changes sweeping the Middle East, local Jews born in Arab lands realize the story isn’t over.

“The best we in the United States could do is let things happen,” Bivas said. “Let their ideas flourish, let them take responsibility for themselves.”

Speaking of her native Tunisia, Uzan could be speaking of any Arab country undergoing transition.

“We need to wait and see,” she said. “The Islamist movements have been somewhat contained in the past. From what I heard the Jews in Tunis are feeling a little insecure right now, and that’s sad.”

Read article here

October 24, 2011

J Weekly of Northern California September 15, 2011 By Dan Pine Bay Area Jews from Egypt, Libya and Tunisia worry about their former Arab homelands As Tahrir Square filled with hundreds of thousands of Egyptians, all demanding liberty, equality and fraternity, the world looked on in amazement. The so-called Arab Spring, which began last December, […]

Read more

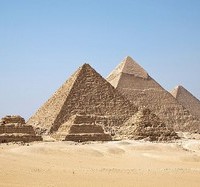

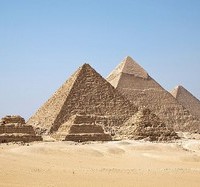

Posted on [caption id="attachment_1064" align="alignleft" width="150" caption="Photo by: Ricardo Liberato"]

Posted on [caption id="attachment_1064" align="alignleft" width="150" caption="Photo by: Ricardo Liberato"] [/caption]

[/caption]

The Jerusalem Post - December 20, 2010

We owe our Egyptian Jewish brothers an apology for what was inflicted upon them.

It was at the café overlooking the Baron Empain Palace in Greater Cairo that I met for the first time recently with “Uncle Elie.” His full name is Elie Amin Kheder, and he is one of tens of thousands of Egyptian Jews who were forced out of their homeland by Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser’s regime in the wake of the 1967 defeat.

Uncle Elie settled in the United States and I had come to “know” him via the Internet – blessed be its innovator. We had corresponded for a long time, and he was my fellow guest on several editions of Al-Hakika (the Truth), a talk show aired on the Egyptian satellite station “Dream,” where we discussed Egypt’s Jewish community. He was always firm and clear in countering all the baseless lies that have long stained one of Egypt’s noblest religious communities, the Karaite Jews.

Over the years, Uncle Elie had told me about his small family – he, his wife Mona, and their son, who apparently did not share their enthusiasm for a visit. Unlike his parents, he is evidently not obsessed with nostalgia for Abbaseya, Al-Dhaher, Al-Sakakini and the other old Cairo districts where Jews used to live.

The chemistry between me and Elie and Mona was marvelous from the start. For me, he was no alien, but rather an Egyptian to the core. This was obvious from his body language, his comments and his satiric spirit – ridiculing everything, even himself. Hotel workers who know me from my frequent visits also quickly began dealing with Uncle Elie as though he were any average Egyptian.

I wondered to myself how they would have behaved if they had known he was Jewish. If they had known that he and his family were long ago forced out of their homeland, pariahs, unwanted both by the state and by society, obliged to migrate from a country where at least 10 generations of Uncle Elie’s ancestors had lived. Those roots counted for nothing when he and his family were thrown into jail for the crime of being Jewish, and then coerced into a voyage to the unknown, their passports stamped with the words: “A Journey of No Return.”

For reasons that only God knows, Uncle Elie was born to a Karaite Jewish family, me to a Muslim Sunni and my friend Awny Ramzy to a Coptic Christian one. Why not accept each other and live together in peace and friendship?

BACK TO Uncle Elie’s visit. A luxury car with a professional driver had been placed at his disposal by his boyhood friends. But I insisted that he and Mona ride in my car. I didn’t want to miss a moment of what might be a once-in-a lifetime meeting.

As we started our trip through Cairo streets packed with the customary traffic, I turned on the cassette player, and, fortuitously, it was playing a song by my favorite singer Muhammad Qandil, who passed away in 2004. “Oh my,” Mona exclaimed. “It’s been a very long time since I last heard Qandil. I remember our life in Egypt when I see him in old Arabic movies.”

I’ll admit I was taken by surprise that she knew Qandil. There are millions of Egyptian youths who have no knowledge of our classic and iconic singers.

Uncle Elie and Mona, both in their 60s, were taking in the hubbub, the people, the vehicles, signs, buildings, tunnels and bridges. “As if it’s not Egypt, and I am not me,” I read in his eyes. He was a man from 1950s Egypt, emerging from a black and white movie.

We were on our way to fulfill what Uncle Elie had described ahead of the trip as “a dear wish” – to visit the Moses al-Dar’i Karaite synagogue, in eastern Cairo’s Abbaseya district, the synagogue of his youth.

I had tried in vain to obtain the necessary security permit for us to enter, and no sooner had we arrived at the building than security guards quickly approached to ask us why we were there. I tried to convince them that the man and his wife only wanted to have a look at a place that was dear to them, but they were resolute, directing us to the police station for a permit. While we were negotiating, Uncle Elie and Mona were able to at least catch a glance, and there we left it. It is not prudent to enter the maze of police station bureaucracy in pursuit of “a dear wish”; these institutions are not the right place for fulfilling wishes. We backed down and drove off.

We have been applying double standards for more than half a century and a stupid fascist tone is now escalating, classifying all Jews as Zionists and all Christians as crusaders. Millions of Muslims are quickly mobilized when an extremist, whether from the East or the West, links terrorism to all Muslims. We dismiss such characterizations as both racist and as unacceptable generalization. Yet, we do the same, giving ourselves the right to generalize about others and sometimes antagonize them.

On our way to the house where Uncle Elie was born and raised, near the Sakakini Pasha palace, I asked him what was he feeling at this early stage of his return, and he immediately responded, bitterly: “Why are we made to face this? We were born Jews, but also Egyptians, and rejecting us, is tantamount to removing a chapter of Egypt’s history.”

Then he held his peace. Perhaps he was internalizing the sorry truth that while half a century was enough time for the Germans to repudiate Nazism, for the Italians to throw Fascism into the dustbin of history and for the Japanese to move beyond the tragedy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it was all very different for Egypt and the rest of the Middle East.

UNCLE ELIE and Mona had grown up and met around Sheikh Qamar Street and Sakakini Square, but everything bar the palace, constructed in 1897, had changed since their day.

Built by Habib Sakakini Pasha, a Jew of Levantine origin whose family migrated to Egypt in the mid-19th century when he was 16, the palace was constructed in the style of a grand edifice he had seen on his travels in Italy and located in what were then the outskirts of Fatimid and Mamluk Cairo. As the slum neighborhoods expanded, it found itself ever closer to the heart of the overpopulated capital. Though encircled today by garbage-strewn, matchbox-style, high-rises, the palace has somehow maintained its grandeur.

Searching for the house where Uncle Elie had lived, we asked a young man working at a shop on Sheikh Qamar Street for guidance. It turned out that Uncle Elie had lived at this very address, but the original building had been demolished and replaced.

An adjacent French bakery where the family had shopped was still here, though. Uncle Elie recalled the special loaves it had produced for Jewish festivals. There is no demand for them today; one would not now find a single surviving Jew in the area.

While Uncle Elie took photographs of his former neighborhood and Mona toured the Sakakini palace, I visualized the two of them here in their 20s, helped by a “soundtrack” of songs by the late Egyptian singer Laila Morad which was echoing from afar: she a charming and alluring young woman, he an exuberant young man, intent on enjoying life.

At that moment, an elderly local man, Amm Jihad, appeared. He claimed (imagined) to have recognized Uncle Elie, and volunteered to guide us around the neighborhood, focusing his narrative on the changes that had taken place here and nationwide since the officers’ coup of July 1952 that paved the way for Nasser to take power four years later.

Amm Jihad seemed to remember every building like his own home: That was where the Samhoun family had lived. At the end of the street was the Isaacs’ home. Here was the school the Jews had established, with the Stars of David still recognizable on its façade and walls. And there was an abandoned house, still standing only because its Jewish heirs overseas were contesting ownership.

Addressing Elie and Mona in the language of simple Cairene, he said: “You were the best. Your days were the most beautiful.”

The modern era, its intruders and developments, he said, had spoiled everything.

How sad it was, I added, that the former Egypt of coexistence, not only between Jews and Muslims, but between all Egyptians from different strands and even foreign communities such as Armenians, Greek, Italians and others, had been abducted by adventurers, clowns and propagandists.

PERSONALLY, I believe we owe our Egyptian Jewish brothers an apology for what was inflicted upon them, for the demise of an authentic Egyptian sect that has roots dating back the time of the Prophet Moses. Its members contributed to Egypt’s renaissance in economics, literature and law – all the manifestations of life. But these contributions were not enough to save them from nationalistic and religious maniacs.

We could have provided the necessary ambiance for them to stay within the country. We had never been in enmity with Judaism nor should we have been. Such enmity is not humane. As far as I know, it is also rejected by Islamic Shari’a law.

The latest official statistics, which date from 2003, indicated that 4,088 Jews still live in Egypt. Until 1952, that number was as many as 100,000.

Cairo’s prestigious Al-Maady district was established by the Jewish company Al-Delta. That’s why the area’s main streets still bear the names of Jewish families such as Sawares and Qatawi. It was a Jewish scholar who pioneered the study of fine arts in Egypt at the start of the 20th century, and also founded the vegetable marketplace in the district of Bab el-Louk, an architectural masterpiece.

Local Jews helped pioneer the modern shopping malls here, through brands such as Omar Effendi, Sidnawi, Cicurel and Shamla. Yacoub Sannou was known as “the father of Egyptian theater.” The Mosairy and Edward Levy companies were central to production and distribution in the local film industry. Togo Misrahi was a leading director; Lilian Levy Cohen, “Kamilia,” was a star actress, as was Rachel Abraham Levy, known as Raqia Ibrahim. Negma Ibrahim participated in plays whose revenue was dedicated to the Egyptian army.

Nazira Mousa Shehata, nicknamed Nagwa Salem, was the only Egyptian artist to win the “Jihad” shield for her role during the War of Attrition. Then there was the legendary singer Laila Mourad, her musician brother Munir and the great artist Dawoud Hosni.

This talk about Egypt’s Jews, prompted by Uncle Elie’s visit, is not mere nostalgia for a bygone era that certainly will not return. Rather, it is a cause for reflection.

We have to learn from our errors, as all civilized nations do, including the Germans, the Italians and the Japanese. Otherwise, our descendants will pay the price. And the first step is to end the blame game and acknowledge: Yes, where Egypt’s Jews are concerned, we made a mistake.

The writer is an Egyptian journalist and political analyst.December 21, 2010

The Jerusalem Post – December 20, 2010 We owe our Egyptian Jewish brothers an apology for what was inflicted upon them. It was at the café overlooking the Baron Empain Palace in Greater Cairo that I met for the first time recently with “Uncle Elie.” His full name is Elie Amin Kheder, and he is […]

Read more

Posted on Huffington Post - June 12th, 2011

David Harris

Executive Director, AJC; Senior Associate, St. Antony's College, Oxford University

I read with dismay the reports of repeated assaults on Copts in Egypt.

Here's a Wall Street Journal account (June 11):

Five weeks after the fall of the Egyptian regime, Ayman Anwar Mitri's [a member of the Christian Coptic minority] apartment was torched. When he showed up to investigate, he was bundled inside by bearded Islamists...[who] accused him of having rented the apartment - by then unoccupied - to loose Muslim women...They beat him with the charred remains of his furniture. Then, one of them produced a box cutter and...amputated Mr. Mitri's right ear. "When they were beating me, they kept saying: 'We won't leave any Christians in this country,'" Mr. Mitri recalled in a recent interview.

Earlier reports this year spoke of a destroyed church in Soul, 20 miles from Cairo, and the mass evacuation of Christians from the village, as well as the New Year's Day bombing of an Alexandria church, leaving 25 Christians dead and scores wounded. And that's only for starters.

Discrimination, distrust, and paranoia feed the troubling climate. Rumors spread like wildfire. A Christian has allegedly abducted a Muslim and tattooed her with a cross. A Muslim disappears and Christians are accused of violence. An intermarriage triggers fear that Christians are trying to subvert the majority population.

Egypt, of course, has been heavily in the political news in recent months. Unrest in the streets led to the ouster of President Hosni Mubarak. The spirit of Tahrir Square captured the imagination of many. Talk of a new dawn in Egypt has been widespread.

But if a page is to be turned in the Arab world's most populous country, it cannot come at the expense of a vulnerable minority. Copts have lived in Egypt for nearly 2,000 years and represent the largest Christian minority in the Middle East, comprising ten percent of Egypt's 83 million inhabitants.

While some Egyptians, to their credit, have spoken bravely of national unity between Muslims and Copts, they have not been able to stop the deadly assaults or lessen the widespread fear.

As a Jew, I identify with the Copts' situation.

Perhaps it's because we can write a doctoral thesis on the topic of minority status. We know all too well what it means to live in a country where legal protections are left to the whim of the authorities, not embedded in a country's DNA or democratic architecture.

Indeed, according to the 1971 constitution, Islam is Egypt's state religion. Nine years later, the state added that the religious principles of Islamic jurisprudence are the principal source of national legislation.

The story of the Copts is all too familiar.

Jews not so long ago also resided in the Arab world. Their roots stretched back hundreds, if not thousands, of years. They actively contributed to the societies in which they lived. But today, with notable exceptions in Morocco and, to a lesser degree, Tunisia, the Jews are essentially gone, driven out by the same forces that today threaten the Copts.

Arab apologists tried to blame the Jewish exodus on the "born-in-sin" Israel, the "all-powerful-and-scheming" Zionists, the "duplicitous" Jews themselves -- anyone who'd go over well as a scapegoat for local consumption but the real culprits. Now, in eerily familiar fashion, the blame is being placed on Christians for their own misfortunes, as if they brought it upon themselves. National introspection has been in short supply.

Take my wife's family.

They had lived in Libya for centuries. Even as most Jews fled the country after the deadly pogroms of 1945 and 1948, they stayed. They wanted to believe that the new Libya, established in 1951, would abide by the minority protections in the constitution. They were dead wrong.

They were treated as second-class residents. And in 1967, there were more attacks on Jews. Ten people -- parents, my wife and her seven siblings, the youngest just three years old -- went into hiding for two weeks, having been threatened with torching by a raging mob. They were saved, it should be said, by a courageous Libyan Muslim. Yet, 44 years later, his identity still cannot be revealed, lest his family be harmed for the act of saving Jews.

In the end, some 800,000 Jews fled their ancestral lands in the second half of the 20th century, but there was hardly a peep from the international community. The UN kept silent. Democratic governments, hypnotized by the lure of oil and markets, averted their gaze. The churches, intimidated or just plain indifferent, were mum. Leading media didn't find the stories of Jews on the move -- so what else is new? -- fit to print.

Maybe had the Jewish story been told, it would have led to greater effort to safeguard the remaining minorities, especially Christians. After all, once the Jews were gone, it wasn't hard to predict who the next targeted population would be.

Apropos, in the old Soviet days, the story goes, a venerated Armenian leader lay on his deathbed. The elders gathered to hear his last words of sage advice. Summoning the last ounce of energy, he whispered, "Save the Jews." Those around him were puzzled by the unexpected advice. They asked him what he meant. "Save the Jews, you fools," he sputtered. "If Stalin finishes them off, we'll be next."

Today, it's not about the Jews but the Christians. Yet, strangely there's a sense of "déjà vu all over again."

Will the world react any differently? There's a huge opportunity. Egypt is redefining itself in the post-Mubarak era. Which way will it turn -- towards enlightenment or darkness? Western nations, led by the United States, have declared Egypt's future a top priority. That means tons of development assistance, not to mention encouragement of investments, exchanges, and tourism.

Clearly, there need to be conditions attached. Christians must be protected in every sense. They are in Egypt by right, not sufferance. They are full citizens, not transients. They deserve equal protection under the law. In other words, they are a barometer by which the "new" Egyptian society will be measured.

No one spoke for the Jews when they were driven out. It's high time to speak out for the Christians. In reality, we're all in this together.

Click here for articleJune 14, 2011

Earlier reports this year spoke of a destroyed church in Soul, 20 miles from Cairo, and the mass evacuation of Christians from the village, as well as the New Year’s Day bombing of an Alexandria church, leaving 25 Christians dead and scores wounded. And that’s only for starters.

Discrimination, distrust, and paranoia feed the troubling climate. Rumors spread like wildfire. A Christian has allegedly abducted a Muslim and tattooed her with a cross. A Muslim disappears and Christians are accused of violence. An intermarriage triggers fear that Christians are trying to subvert the majority population.

Read more

Posted on Huffington Post - February 18, 2011

Rabbi Abraham Cooper

Associate dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and its Museum of Tolerance

Let's face it. The people's revolt in the streets of Egypt caught everyone by surprise and so-called experts and pundits are still scrambling to contextualize it and prophesy about the nation's future.

But the 18-day drama proved that revolutions are messy -- even ones birthed on Google and sustained by Facebook and Twitter. Ask CNN's Anderson Cooper or FOX News' Gregg Palkot, who were among the journalists attacked in Tahrir Square.

Now comes belated word of the brutal mob sexual assault on Lara Logan, a veteran correspondent covering for CBS' 60 Minutes during the jubilant celebration over Hosni Mubarak's ouster. The network had apparently made a decision not to go public about the incident and released details only after it was clear that other media would break the story.

It was painful listening to CBS's description of the horrors the mother of two suffered after she was separated from her crew and assaulted. Thank G-d she was finally rescued and we pray for her full recovery.

But it is a shame that CBS omitted one important detail from their release: The 200 member mob was screaming "Jew, Jew" during their vicious attack. Logan is not Jewish.

Why is this important? Because the issue isn't just the hate of one frenzied mob, but a society's mindset. For in today's Egypt, a nation searching for its 21st century identity, there is no more vile a curse that you can hurl at someone than to call him or her a Jew. A dangerous exaggeration? I don't think so: A 2010 Pew Poll confirmed that 95 percent of Egyptians hold negative views about Jews. That fact may help explain why simultaneously there were anti-Mubarak protesters holding posters with President Mubarak's face covered by the reviled Star of David, even as pro-Mubarak forces depicted western media as spies for Israel and protesters as agents of "outside forces." And who might those sinister forces be? A few years back, official Egyptian state television ran a 41-part series during Ramadan titled "Horseman without A Horse" based on the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the vicious Czarist-era conspiratorial screed swallowed whole by large swaths of Arabs and Muslims "proving" that Jews lurk behind every evil in the world. Officially sanctioned anti-Semitism, the popular negative stereotypes ingrained in books, combined with the hatred of the Muslim Brotherhood, make the Jew Egypt's poster child for all things hated or feared.

Of course, there are other voices that need to be heard and whose messages need to be nurtured. I am thinking of Abed (pseudonym), a young activist with whom I have exchanged e-mails and who was held and tortured by authorities for three of those 18 tumultuous days. He repeatedly emphasized that for the young people on the street, this revolution is not against or even about Jews or Israel. He urged Israelis and other Jews to speak out on behalf of people like himself who put their lives on the line for a democratic and peaceful future. Of course, he is right and the Simon Wiesenthal Center and virtually every other Jewish organization has done so. As Simon Wiesenthal often said: "Where democracy is strong, it is good for Jews and where it is weak, it is bad for the Jews".

But Egypt's future will not be secured only through free and open elections but by a new civil society that will be powerful enough to safeguard religious minorities and begin to deconstruct the culture of anti-Jewish hate. President Obama is right when he says we should back democracy-building in Egypt, but our financial aid and diplomatic support should be bestowed only upon those elements committed to combating, not leveraging, anti-Semitism. The media, which played a pivotal role in the people's revolution, must now lead the way in exposing, not avoiding the pervasive anti-Jewish culture of hate and religious intolerance. Failure to do so will doom hopes for a democratic Egypt and help pave the way for an ultimate Muslim Brotherhood takeover.

See article hereJune 13, 2011

Let’s face it. The people’s revolt in the streets of Egypt caught everyone by surprise and so-called experts and pundits are still scrambling to contextualize it and prophesy about the nation’s future.

But the 18-day drama proved that revolutions are messy — even ones birthed on Google and sustained by Facebook and Twitter. Ask CNN’s Anderson Cooper or FOX News’ Gregg Palkot, who were among the journalists attacked in Tahrir Square.

Read more

Posted on Foreign Policy - April 25th, 2011

Beaches and bikinis from when Alexandria was Club Med

Courtesy of Elie Moreno

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="581" caption="When Alexandria was Club Med"] [/caption]

In 1959, Elie Moreno, then a 19-year-old sophomore engineering student at Purdue University in Indiana, visited the Egyptian port city of Alexandria on his summer vacation, and brought his camera. Moreno, an Egyptian of Sephardic Jewish descent, had been born in Alexandria and raised in Cairo. But the Egypt in which he had grown up, the milieu of the country's multi-ethnic urban elite, was fast disappearing; the summer of 1959 was the last Moreno would see of it.

The late 1950s marked the end of an era in Alexandria that had begun in the late 19th century, when the port -- then the largest on the eastern Mediterranean -- emerged as one of the world's great cosmopolitan cities. Europeans -- Greeks, Italians, Armenians, and Germans -- had gravitated to Alexandria in the mid-19th century during the boom years of the Suez Canal's construction, staying through the British invasion of the port in 1882 and the permissive rule of King Farouk in the 1930s and 1940s. Foreign visitors and Egyptians alike flocked to the city's beaches in the summers, where revealing bathing suits were as ordinary as they would be extraordinary today.

But by midcentury, King Farouk -- a lackadaisical ruler in the best of times -- had grown deeply unpopular among Egyptians and was deposed in a CIA-backed coup in 1952. Cosmopolitan Alexandria's polyglot identity -- half a dozen languages were spoken on the city's streets -- and indelible links to Egypt's colonial past were an uncomfortable fit with the pan-Arab nationalism that took root under President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the late 1950s and 1960s. "[W]hat is this city of ours?" British novelist Lawrence Durrell, who served as a press attaché in the British Embassy in Alexandria during World War II, wrote despairingly in 1957 in the first volume of The Alexandria Quartet, his tetralogy set in the city during its heyday as an expatriate haven. "In a flash my mind's eye shows me a thousand dust-tormented streets. Flies and beggars own it today -- and those who enjoy an intermediate existence between either." By the time of Hosni Mubarak's rule (and largely in response to his secularism), Egypt's second-largest city had become synonymous with devout, and deeply conservative, Islam.

The pictures from Moreno's collection, taken on the 1959 visit and several beach trips in previous years, capture the last days of an Alexandria that would be all but unrecognizable today, in which affluent young Egyptians of Arab, Sephardic, and European descent frolic in a landscape of white sand beaches, sailboats, and seaside cabanas. Two years later, in 1961, the structural steel company Moreno's father ran was nationalized by Nasser, and his family left for the United States shortly thereafter. Moreno, who went on to found a semiconductor company in Los Angeles, wouldn't visit his birthplace until he was well into middle age.

But the memories aren't all bittersweet. The woman on the far left in the above photograph, taken on Alexandria's Mediterranean coast in 1955, is Odette Tawil, whom Moreno first met in Alexandria in the summer of 1959. Reunited in the United States years later, they visited Egypt together in 1998, to get married.

For full photo essay, click hereJune 14, 2011

[/caption]

In 1959, Elie Moreno, then a 19-year-old sophomore engineering student at Purdue University in Indiana, visited the Egyptian port city of Alexandria on his summer vacation, and brought his camera. Moreno, an Egyptian of Sephardic Jewish descent, had been born in Alexandria and raised in Cairo. But the Egypt in which he had grown up, the milieu of the country's multi-ethnic urban elite, was fast disappearing; the summer of 1959 was the last Moreno would see of it.

The late 1950s marked the end of an era in Alexandria that had begun in the late 19th century, when the port -- then the largest on the eastern Mediterranean -- emerged as one of the world's great cosmopolitan cities. Europeans -- Greeks, Italians, Armenians, and Germans -- had gravitated to Alexandria in the mid-19th century during the boom years of the Suez Canal's construction, staying through the British invasion of the port in 1882 and the permissive rule of King Farouk in the 1930s and 1940s. Foreign visitors and Egyptians alike flocked to the city's beaches in the summers, where revealing bathing suits were as ordinary as they would be extraordinary today.

But by midcentury, King Farouk -- a lackadaisical ruler in the best of times -- had grown deeply unpopular among Egyptians and was deposed in a CIA-backed coup in 1952. Cosmopolitan Alexandria's polyglot identity -- half a dozen languages were spoken on the city's streets -- and indelible links to Egypt's colonial past were an uncomfortable fit with the pan-Arab nationalism that took root under President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the late 1950s and 1960s. "[W]hat is this city of ours?" British novelist Lawrence Durrell, who served as a press attaché in the British Embassy in Alexandria during World War II, wrote despairingly in 1957 in the first volume of The Alexandria Quartet, his tetralogy set in the city during its heyday as an expatriate haven. "In a flash my mind's eye shows me a thousand dust-tormented streets. Flies and beggars own it today -- and those who enjoy an intermediate existence between either." By the time of Hosni Mubarak's rule (and largely in response to his secularism), Egypt's second-largest city had become synonymous with devout, and deeply conservative, Islam.

The pictures from Moreno's collection, taken on the 1959 visit and several beach trips in previous years, capture the last days of an Alexandria that would be all but unrecognizable today, in which affluent young Egyptians of Arab, Sephardic, and European descent frolic in a landscape of white sand beaches, sailboats, and seaside cabanas. Two years later, in 1961, the structural steel company Moreno's father ran was nationalized by Nasser, and his family left for the United States shortly thereafter. Moreno, who went on to found a semiconductor company in Los Angeles, wouldn't visit his birthplace until he was well into middle age.

But the memories aren't all bittersweet. The woman on the far left in the above photograph, taken on Alexandria's Mediterranean coast in 1955, is Odette Tawil, whom Moreno first met in Alexandria in the summer of 1959. Reunited in the United States years later, they visited Egypt together in 1998, to get married.

For full photo essay, click hereJune 14, 2011

In 1959, Elie Moreno, then a 19-year-old sophomore engineering student at Purdue University in Indiana, visited the Egyptian port city of Alexandria on his summer vacation, and brought his camera. Moreno, an Egyptian of Sephardic Jewish descent, had been born in Alexandria and raised in Cairo. But the Egypt in which he had grown up, the milieu of the country’s multi-ethnic urban elite, was fast disappearing; the summer of 1959 was the last Moreno would see of it.

Read more

Posted on Conflicting reports emerge over whereabouts of head of Jewish community in Egypt found guilty of fraud last month.

Posted on Conflicting reports emerge over whereabouts of head of Jewish community in Egypt found guilty of fraud last month.

Carmen Weinstein is safe and sound at home in her native city of Cairo. Carmen Weinstein is in Switzerland on vacation but will soon return to Egypt to prove her innocence of charges of fraud. Carmen Weinstein is a fugitive from the law who fled Egypt in a secret operation by the Mossad to an undisclosed Western country where she has taken refuge.

Over the past two weeks conflicting and sometimes outlandish reports have emerged in the media over the whereabouts of Weinstein, the 82-year-old head of Egypt’s tiny Jewish community, who was recently convicted of fraud in a controversial trial some claim was fixed.

Last week the Egyptian daily Azzaman reported she had left the country in order to avoid a three-year prison sentence for fraud with the help of the Mossad, setting off a flood of anti-Semitic talkbacks on its Website.

However, yesterday the Foreign Ministry which has been monitoring the situation told The Jerusalem Post that the leader of the community which now consists of no more than a few dozen elderly women is still in Cairo.

“She never left,” a spokesman said. “There’s nothing new to report, but we’re satisfied that the media is taking an interest in her case because this is an issue of concern.”

At the same time credible sources in the Egyptian capital said Weinstein was in Switzerland on her annual trip and would be back by the end of the summer for her appeal.

So, where in the world is Carmen Weinstein? The octogenarian did not answer an e-mail inquiry yesterday.

However, Zvi Mazel, a former Israeli ambassador to Egypt, told the Post she was still in Egypt and that he had spoken to her on the phone last week.

According to Mazel, Weinstein’s entire trial was conducted in absentia without her knowledge. According to the indictment, she sold a plot of land on which a synagogue stands to a businessman but after the deal was done she refused to put the deed under his name or return his money.

The judge found her guilty sentencing her to three years in prison and a fine of $1,800.

“There’s a serious suspicion that the claimant rigged it, perhaps bribing an official,” he said. “It seems like there was a trick.” Furthermore, Mazel drew a connection between the recent trial of two Egyptian parliament members accused of forging deeds of Jewish-owned property and the Weinstein case, suggesting it might be a cover up.

“A year ago there was a major trial of two parliament members who were charged alongside a contractor for allegedly forging deeds of five plots owned by the Jewish community,” Mazel said.

“The court found the parliament members innocent but convicted the contractor.

How could it be that the two lawmakers were innocent but the contractor guilty? How could these five Jewish-owned plots be disconnected from the Weinstein case? I therefore raise the suspicion that the Weinstein trial may have been orchestrated to distract public opinion in Egypt from these forgeries.”

In the meantime Weinstein, who is said to be in ill health, is expected to appeal her conviction in an Egyptian court.

“I believe she’s innocent – she must appeal,” Mazel said. “There’s a limit to everything.”

Article SourceSeptember 2, 2010

Carmen Weinstein is safe and sound at home in her native city of Cairo. Carmen Weinstein is in Switzerland on vacation but will soon return to Egypt to prove her innocence of charges of fraud. Carmen Weinstein is a fugitive from the law who fled Egypt in a secret operation by the Mossad to an undisclosed Western country where she has taken refuge.

Over the past two weeks conflicting and sometimes outlandish reports have emerged in the media over the whereabouts of Weinstein, the 82-year-old head of Egypt’s tiny Jewish community, who was recently convicted of fraud in a controversial trial some claim was fixed.

Last week the Egyptian daily Azzaman reported she had left the country in order to avoid a three-year prison sentence for fraud with the help of the Mossad, setting off a flood of anti-Semitic talkbacks on its Website.

However, yesterday the Foreign Ministry which has been monitoring the situation told The Jerusalem Post that the leader of the community which now consists of no more than a few dozen elderly women is still in Cairo.

“She never left,” a spokesman said. “There’s nothing new to report, but we’re satisfied that the media is taking an interest in her case because this is an issue of concern.”

At the same time credible sources in the Egyptian capital said Weinstein was in Switzerland on her annual trip and would be back by the end of the summer for her appeal.

So, where in the world is Carmen Weinstein? The octogenarian did not answer an e-mail inquiry yesterday.

However, Zvi Mazel, a former Israeli ambassador to Egypt, told the Post she was still in Egypt and that he had spoken to her on the phone last week.

According to Mazel, Weinstein’s entire trial was conducted in absentia without her knowledge. According to the indictment, she sold a plot of land on which a synagogue stands to a businessman but after the deal was done she refused to put the deed under his name or return his money.

The judge found her guilty sentencing her to three years in prison and a fine of $1,800.

“There’s a serious suspicion that the claimant rigged it, perhaps bribing an official,” he said. “It seems like there was a trick.” Furthermore, Mazel drew a connection between the recent trial of two Egyptian parliament members accused of forging deeds of Jewish-owned property and the Weinstein case, suggesting it might be a cover up.

“A year ago there was a major trial of two parliament members who were charged alongside a contractor for allegedly forging deeds of five plots owned by the Jewish community,” Mazel said.

“The court found the parliament members innocent but convicted the contractor.

How could it be that the two lawmakers were innocent but the contractor guilty? How could these five Jewish-owned plots be disconnected from the Weinstein case? I therefore raise the suspicion that the Weinstein trial may have been orchestrated to distract public opinion in Egypt from these forgeries.”

In the meantime Weinstein, who is said to be in ill health, is expected to appeal her conviction in an Egyptian court.

“I believe she’s innocent – she must appeal,” Mazel said. “There’s a limit to everything.”

Article SourceSeptember 2, 2010

Conflicting reports emerge over whereabouts of head of Jewish community in Egypt found guilty of fraud last month. Carmen Weinstein is safe and sound at home in her native city of Cairo. Carmen Weinstein is in Switzerland on vacation but will soon return to Egypt to prove her innocence of charges of fraud. Carmen Weinstein is a […]

Read more

Posted on

Posted on  Egypt spent $1.8 million to restore the synagogue and office space where Maimonides once worked and studied in Cairo.

CAIRO — Down a winding alley, deep in a quiet neighborhood of rutted roads and donkey carts, where food vendors sold cheap sandwiches and children chased after a soccer ball, an extraordinary moment passed here with little notice: Jews and Muslims, Israelis and Egyptians sat together and celebrated their shared heritage.

But no one outside the small group of invited guests was allowed to see.

Egypt spent $1.8 million to restore a part of its historic past, the synagogue and office space of Rabbi Moses Ben Maimon, known in the West as Maimonides, the 12th-century physician and philosopher who is considered among the most important rabbinic scholars in Jewish history. On March 7, security men held up a canvas curtain to block the road and barred the news media from attending.

The restoration project, and its muted unveiling, exposed a conundrum Egyptian society has struggled with since its leadership made peace with Israel three decades ago: How to balance the demands of Western capitals and a peace process that relies on Egypt to work with Israel with a public antipathy for Israel.

The efforts to restore the synagogue but keep it quiet illustrate the contortions of a government that often tries to satisfy both demands simultaneously.

“This is an Egyptian monument; if you do not restore a part of your history you lose everything,” said Zahi Hawass, the general secretary of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, which approved and oversaw the project. “I love the Jews, they are our cousins! But the Israelis, what they are doing against the Palestinians is insane. I will do anything to restore and preserve the synagogue, but celebration, I cannot accept.”

Israel opened its embassy in Cairo just over 30 years ago. In that time, the debate over how to deal with Israel has grown more complicated, at times more nuanced, as the government and intellectuals try to navigate between a desire to preserve a cold peace while also bending to pragmatic economic, social and political realities, political analysts said.

There is no appetite in Egypt for normalization of relations. But there has never been a firm definition of where the line should be drawn, and that is where the debate often falls.

Are Egyptian reporters to be barred from interviewing Israeli officials?

Can artists show their works at a show that also showcases Israeli work?

“With regards to relations with Israel, Egyptians generally and Arabs specifically fall in the deep abyss of confusion and doubt and stagger around the boundaries of this relation, where it starts and where it ends,” wrote Salama Ahmed Salama, in the independent daily newspaper Shorouk.

The problem arose when Anwar Sadat decided to strike peace with Israel without also resolving all the other Arab issues. Egyptian intellectuals felt obligated to take a stand in support of Palestinians, so they called for boycotting normalization.

But over the years, the picture has become clouded as Egypt has made economic deals with Israel, sold it natural gas, welcomed Israeli officials and sent Egyptian officials to Israel. It also has become complicated by Al Jazeera, the popular satellite news channel that regularly covers events in Israel and the occupied territories.

Recently, two cases crystallized the public debate. Hala Mustafa, the editor of one of Egypt’s premier political journals, Democracy, was formally censured last month for having met the Israeli ambassador in her office. It was first time the journalists’ syndicate punished a member for defying a ban on normalization since the group was founded in 1941, according to the independent daily newspaper Al Masry Al Youm.

Even some of her critics, who strongly disagree with Ms. Mustafa’s politics, said they were surprised at the selective nature of the condemnation. Singling out Ms. Mustafa said as much about the way the state and state-aligned institutions apply laws and rules, critics said, as it did about widespread hostility to Israel.

“Accountability here is very selective because the law does not prevail over society,” said Magdy el-Gallad, chief editor of Al Masry Al Youm. “The law is there but its enforcement is subject to personal criteria and political settlements and accounts. And this is what we saw in Hala Mustafa’s case.”

No one can say where to draw the line.

Mr. Gallad was willing, for example, to attend a meeting organized by President Obama, even though an Israeli attended, while another popular writer, Fahmy Howeidy, refused.

While Ms. Mustafa was punished, six top Egyptian scholars, including some from the nation’s premier research center, the Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies, attended a conference with the Israeli ambassador. None of them were punished.

When the subject of restoring the synagogue of Maimonides was first raised about two years ago, Egypt agreed to do the work, but asked that it not be made public. The project was announced a year later when the culture minister, Farouk Hosny, was hoping to become the next director general of Unesco, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. When his bid for the post failed, many doubted whether the project would be completed.

But the work was completed, and at first the authorities told members of the Egyptian Jewish community that the news media could not attend the ceremony because they wanted to make the official announcement themselves. Then Dr. Hawass announced he was canceling that, too.

“I am trying to give the Israelis a message that they should make peace,” Dr. Hawass said.

Rabbi Andrew Baker, of the American Jewish Committee, had hoped to publicly congratulate Egyptian officials for the work when he spoke during the ceremony. But his speech was never heard beyond the synagogue walls.

“It’s a sad commentary on the current state of affairs, even if it is not surprising,” Rabbi Baker said in an e-mail message after returning to the United States. “All along in our discussions over the years, they have been fearful of critical voices in Egypt, who conflate criticism of the State of Israel with Egyptian Jews and their heritage. This is a process that has been years in development, and it will not be quickly or easily reversed.”

September 2, 2010

Egypt spent $1.8 million to restore the synagogue and office space where Maimonides once worked and studied in Cairo.

CAIRO — Down a winding alley, deep in a quiet neighborhood of rutted roads and donkey carts, where food vendors sold cheap sandwiches and children chased after a soccer ball, an extraordinary moment passed here with little notice: Jews and Muslims, Israelis and Egyptians sat together and celebrated their shared heritage.

But no one outside the small group of invited guests was allowed to see.

Egypt spent $1.8 million to restore a part of its historic past, the synagogue and office space of Rabbi Moses Ben Maimon, known in the West as Maimonides, the 12th-century physician and philosopher who is considered among the most important rabbinic scholars in Jewish history. On March 7, security men held up a canvas curtain to block the road and barred the news media from attending.

The restoration project, and its muted unveiling, exposed a conundrum Egyptian society has struggled with since its leadership made peace with Israel three decades ago: How to balance the demands of Western capitals and a peace process that relies on Egypt to work with Israel with a public antipathy for Israel.

The efforts to restore the synagogue but keep it quiet illustrate the contortions of a government that often tries to satisfy both demands simultaneously.

“This is an Egyptian monument; if you do not restore a part of your history you lose everything,” said Zahi Hawass, the general secretary of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, which approved and oversaw the project. “I love the Jews, they are our cousins! But the Israelis, what they are doing against the Palestinians is insane. I will do anything to restore and preserve the synagogue, but celebration, I cannot accept.”

Israel opened its embassy in Cairo just over 30 years ago. In that time, the debate over how to deal with Israel has grown more complicated, at times more nuanced, as the government and intellectuals try to navigate between a desire to preserve a cold peace while also bending to pragmatic economic, social and political realities, political analysts said.

There is no appetite in Egypt for normalization of relations. But there has never been a firm definition of where the line should be drawn, and that is where the debate often falls.

Are Egyptian reporters to be barred from interviewing Israeli officials?

Can artists show their works at a show that also showcases Israeli work?

“With regards to relations with Israel, Egyptians generally and Arabs specifically fall in the deep abyss of confusion and doubt and stagger around the boundaries of this relation, where it starts and where it ends,” wrote Salama Ahmed Salama, in the independent daily newspaper Shorouk.

The problem arose when Anwar Sadat decided to strike peace with Israel without also resolving all the other Arab issues. Egyptian intellectuals felt obligated to take a stand in support of Palestinians, so they called for boycotting normalization.

But over the years, the picture has become clouded as Egypt has made economic deals with Israel, sold it natural gas, welcomed Israeli officials and sent Egyptian officials to Israel. It also has become complicated by Al Jazeera, the popular satellite news channel that regularly covers events in Israel and the occupied territories.

Recently, two cases crystallized the public debate. Hala Mustafa, the editor of one of Egypt’s premier political journals, Democracy, was formally censured last month for having met the Israeli ambassador in her office. It was first time the journalists’ syndicate punished a member for defying a ban on normalization since the group was founded in 1941, according to the independent daily newspaper Al Masry Al Youm.

Even some of her critics, who strongly disagree with Ms. Mustafa’s politics, said they were surprised at the selective nature of the condemnation. Singling out Ms. Mustafa said as much about the way the state and state-aligned institutions apply laws and rules, critics said, as it did about widespread hostility to Israel.

“Accountability here is very selective because the law does not prevail over society,” said Magdy el-Gallad, chief editor of Al Masry Al Youm. “The law is there but its enforcement is subject to personal criteria and political settlements and accounts. And this is what we saw in Hala Mustafa’s case.”

No one can say where to draw the line.

Mr. Gallad was willing, for example, to attend a meeting organized by President Obama, even though an Israeli attended, while another popular writer, Fahmy Howeidy, refused.

While Ms. Mustafa was punished, six top Egyptian scholars, including some from the nation’s premier research center, the Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies, attended a conference with the Israeli ambassador. None of them were punished.

When the subject of restoring the synagogue of Maimonides was first raised about two years ago, Egypt agreed to do the work, but asked that it not be made public. The project was announced a year later when the culture minister, Farouk Hosny, was hoping to become the next director general of Unesco, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. When his bid for the post failed, many doubted whether the project would be completed.

But the work was completed, and at first the authorities told members of the Egyptian Jewish community that the news media could not attend the ceremony because they wanted to make the official announcement themselves. Then Dr. Hawass announced he was canceling that, too.

“I am trying to give the Israelis a message that they should make peace,” Dr. Hawass said.

Rabbi Andrew Baker, of the American Jewish Committee, had hoped to publicly congratulate Egyptian officials for the work when he spoke during the ceremony. But his speech was never heard beyond the synagogue walls.

“It’s a sad commentary on the current state of affairs, even if it is not surprising,” Rabbi Baker said in an e-mail message after returning to the United States. “All along in our discussions over the years, they have been fearful of critical voices in Egypt, who conflate criticism of the State of Israel with Egyptian Jews and their heritage. This is a process that has been years in development, and it will not be quickly or easily reversed.”

September 2, 2010

Egypt spent $1.8 million to restore the synagogue and office space where Maimonides once worked and studied in Cairo. CAIRO — Down a winding alley, deep in a quiet neighborhood of rutted roads and donkey carts, where food vendors sold cheap sandwiches and children chased after a soccer ball, an extraordinary moment passed here with […]

Read more

Posted on

Author Lucette Lagnado, who chronicled her family’s exodus from Egypt in 1963, reflects on the current situation in Cairo.

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

Caroline Lagnado

The Jewish Week

Lagnado Family in Egypt, circa 1952

With the situation in Egypt remaining fluid and complex, little attention has been paid to the country’s recent history and the effects of its last revolution. While Egypt was once home to thousands of Jews, including my family, they largely left the country in the wake of the 1952 revolution.

Growing up, I heard many stories about the Cairo that my father and his family had to leave behind. Theirs was a city of European private schools, cafés and a comfortable Jewish life. This all changed when Gamel Abdel Nasser overthrew the monarchy, and all foreigners, including Jews, were forced to leave. My family remained until 1963, in part because my father’s younger sister, Lucette, was born in 1956, but also in the hope that things would improve.

The years between the revolution and their departure were difficult ones. My father, Ezra Cesar, and his Jewish friends were picked on at school, and my grandfather, Leon, lost access to his stocks. During the 1952 revolution my father recalls having to keep the windows in their home shut, and in the ensuing years, walking fearfully outside, anxious not to be attacked. Remarkably, while many cinemas and hotels were burned to the ground, most of their synagogues remained standing, and still do.

Egyptian Jewish refugees around the world have been, like Egypt’s protesters, communicating via the Internet, wondering how this will further affect the country they left behind. For some perspective, I discussed the situation with my aunt, the noted writer Lucette Lagnado, whose best seller, “The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit,” described our family’s modern-day exodus from Egypt. She is now working on a follow-up memoir.

How will your next book be affected by the revolution in Egypt?

My new book, “The Arrogant Years,” a companion memoir to “Sharkskin,” which will be out this fall, returns to the familiar territory of Cairo versus New York. Suddenly, the lessons of the 1952 revolution seem awfully relevant to what is going on.

You have a chapter in “Sharkskin” called “The Last Days of Tarboosh,” which deals with the fires and mayhem of the 1952 revolution. How did you feel when you heard about the recent violent incidents?

It brought back terrible memories, or rather inherited memories since I wasn’t born at the time of the revolution but I heard stories and I have read a great deal about the mayhem that swept the country back then, so I became very sad to see it happening again. In 1952 foreign outposts were the targets — any shops owned by Jews or Brits or foreigners were fair game as were the cinemas and hotels. Now the foreigners and Jews were gone so what did they destroy? Police stations and other shops; it was incredibly sad to watch actually.

Now of course the revolution of 2011 is on its face very different — generated by the youth of the country with a rush of idealism, which was by no means the case in 1952. But I think there is a Pollyanna-ish element to the way some of us have looked at the events of recent weeks. As with 1952 I worry that it will be hijacked by insidious forces, that there will be a repeat of history— a dictatorship or even a worse dictatorship than the one the Egyptians suffered through the last 60 years.

Your father is the protagonist of “Sharkskin.” Have you thought about how he would react to what is going on?