Posted on

Posted on The Jerusalem Post – January 17, 2011

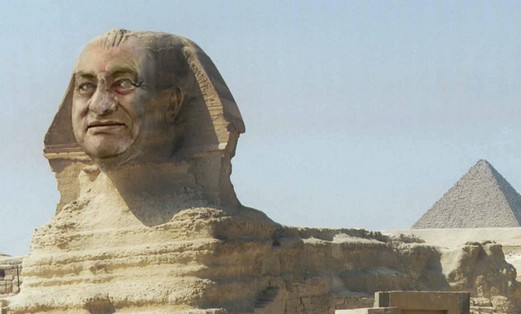

Photo by: avi katz

Jewish Communities have existed in the land of Egypt for thousands of years despite the three prohibitions against returning to Egypt mentioned in the Torah. Egypt has been both a place of “enslavement” and a place of refuge for the Jewish People. All Jews know the story of the Exodus, but perhaps not everyone knows that Egypt has also been a tolerant safe haven during times of persecution. Wave after wave of Jews settled in Egypt after fleeing or being expelled from other lands. The most notable influx of refugees brought the great Maimonides to Egypt. He and his family were fleeing from the ruthless Almohad Caliphate which conquered portions of Southern Spain and North Africa. Egypt became an important center of Jewish thought, and many Talmudic Schools were established there.

In more recent times, Egypt has also been a place of refuge for Jews fleeing the various pogroms in Europe. The result of all of this immigration was a very large and diverse Jewish Community. Arab Rabbanite, Sephardic, Karaite, and Ashkenazi Communities flourished in Egypt, mostly in the cities of Cairo and Alexandria. By 1922, the Jewish population of Egypt was estimated to be 80,000 people.

And then things changed. During the 1930’s, with the Arab-Jewish fighting in British Occupied Eretz Yisrael and the rise of Nazi Germany, relations between Jewish and Egyptian Society became strained. By the 1940’s, the situation worsened and pogroms took place from 1942 onwards. The founding of the State of Israel in 1948 marked a period of all out war against the Jewish Community. Bombings in Jewish areas claimed 70 lives and injured hundreds more. Riots claimed many more Jewish lives. Jewish property and businesses were confiscated by the Egyptian Government, and Jewish males between the ages of 17 and 60 were forcibly expelled. The Jewish population of Egypt began to dwindle as people fled from their homeland to find refuge in the new State of Israel, Brazil, France, the United States, and Argentina. As of 2004, the Jewish population of Egypt was estimated to be 100 people. The last Jewish wedding in Egypt took place in 1984. To this day, there is strong anti-Jewish sentiment in Egypt, especially in the media. The glory days of the Rambam are no more, and only two synagogues exist in the entire country.

The proud Jews of the Second Exodus have brought their culinary traditions out of Egypt. Their cuisine, like the cuisine of Egypt as a whole, is quite humble and delicious. Grains and legumes figure very prominently in their cooking. Falafel, an Israeli favorite, is Egyptian in origin. Fragrant stews and pulses form the backbone of the cuisine, but there is no shortage of fish, lamb, and poultry dishes. Desserts are ever present and seductively sweet.

Lately I have been eating breakfast the way the Egyptians do. I have Ful Mudammas. It is a simple preparation of small, dried fava beans, red lentils, onion, and tomato. This may not sound very interesting, but trust me, it is. The basic Ful is just a healthy, fiber-rich catalyst. The real magic is in the multitude of condiments that can be served with the Ful. I start my mornings with hot sauce, olive oil, and tahina. Sometimes I go for the fried egg option with kashk and sumac. Even a simple drizzle of salted butter raises the Ful to new levels of good!

Ful not only gets your tongue dancing, it is healthy, and will stick with you for most of the day. It is like throwing a big log on your metabolic fire. No quick burn and crash here, this stuff keeps you going strong.

Ful also makes a great Shabbat dish. Think of it as Egyptian Cholent/Hamin. By simply adding whole eggs in their shell, you achieve a traditional Egyptian Jewish Shabbat meal.

Preparing Ful requires some planning. The beans must be soaked for 24 hours. The dish itself needs to cook for at least 12 hours, but it is better after 18 hours. The good news is that you can make it in a slow cooker overnight. Then it is ready by breakfast time. Once made, the Ful can be stored in the refrigerator for up to a week, and reheated in the microwave as needed. The longer it sits, the better it gets!

Here is the recipe that I use. It is very traditional, but with a few personal touches. This recipe will make quite a large batch, so feel free to cut it in half if you need to.

Ful Muddamas

Ingredients

3 pounds small dried fava beans*, soaked overnight in the refrigerator

1 cup red lentils, rinsed

1 onion, chopped

2 tomatoes, chopped

2 1/2 quarts vegetable stock or water

1 tablespoon hot sauce (your favorite, optional)

1 tablespoon kosher salt (optional, traditionally Ful is not salted until served)

Whole eggs in the shell (optional, for Shabbat)

Directions

1. Place all ingredients into a slow cooker. Cook on High for 2 hours.

2. Turn temperature down to low and cook for 10 to 16 hours.

3. Serve in a bowl with your favorite condiments and plenty of whole grain flat-breads.

If you do not have a slow cooker, start Ful on top of stove in a heavy pot. Bring to a boil, cover, and place in a 200 degree oven for 12 to 18 hours.

Here are some of the traditional garnishes for Ful Mudammas, but feel free to try your own:

hot sauce, olive oil, tahina, hummus, tomato sauce, kashk, butter, garlic sauce, fried egg, hard-cooked egg, chick peas, green onions, and sumac.

* Small fava beans can be found in most Arab or Persian stores, or on-line.

In a pinch, you can substitute regular, brown lentils. This of course is not traditional, and probably will ruffle some purist feathers.February 1, 2011

Photo by: avi katz

Jewish Communities have existed in the land of Egypt for thousands of years despite the three prohibitions against returning to Egypt mentioned in the Torah. Egypt has been both a place of “enslavement” and a place of refuge for the Jewish People. All Jews know the story of the Exodus, but perhaps not everyone knows that Egypt has also been a tolerant safe haven during times of persecution. Wave after wave of Jews settled in Egypt after fleeing or being expelled from other lands. The most notable influx of refugees brought the great Maimonides to Egypt. He and his family were fleeing from the ruthless Almohad Caliphate which conquered portions of Southern Spain and North Africa. Egypt became an important center of Jewish thought, and many Talmudic Schools were established there.

In more recent times, Egypt has also been a place of refuge for Jews fleeing the various pogroms in Europe. The result of all of this immigration was a very large and diverse Jewish Community. Arab Rabbanite, Sephardic, Karaite, and Ashkenazi Communities flourished in Egypt, mostly in the cities of Cairo and Alexandria. By 1922, the Jewish population of Egypt was estimated to be 80,000 people.

And then things changed. During the 1930’s, with the Arab-Jewish fighting in British Occupied Eretz Yisrael and the rise of Nazi Germany, relations between Jewish and Egyptian Society became strained. By the 1940’s, the situation worsened and pogroms took place from 1942 onwards. The founding of the State of Israel in 1948 marked a period of all out war against the Jewish Community. Bombings in Jewish areas claimed 70 lives and injured hundreds more. Riots claimed many more Jewish lives. Jewish property and businesses were confiscated by the Egyptian Government, and Jewish males between the ages of 17 and 60 were forcibly expelled. The Jewish population of Egypt began to dwindle as people fled from their homeland to find refuge in the new State of Israel, Brazil, France, the United States, and Argentina. As of 2004, the Jewish population of Egypt was estimated to be 100 people. The last Jewish wedding in Egypt took place in 1984. To this day, there is strong anti-Jewish sentiment in Egypt, especially in the media. The glory days of the Rambam are no more, and only two synagogues exist in the entire country.

The proud Jews of the Second Exodus have brought their culinary traditions out of Egypt. Their cuisine, like the cuisine of Egypt as a whole, is quite humble and delicious. Grains and legumes figure very prominently in their cooking. Falafel, an Israeli favorite, is Egyptian in origin. Fragrant stews and pulses form the backbone of the cuisine, but there is no shortage of fish, lamb, and poultry dishes. Desserts are ever present and seductively sweet.

Lately I have been eating breakfast the way the Egyptians do. I have Ful Mudammas. It is a simple preparation of small, dried fava beans, red lentils, onion, and tomato. This may not sound very interesting, but trust me, it is. The basic Ful is just a healthy, fiber-rich catalyst. The real magic is in the multitude of condiments that can be served with the Ful. I start my mornings with hot sauce, olive oil, and tahina. Sometimes I go for the fried egg option with kashk and sumac. Even a simple drizzle of salted butter raises the Ful to new levels of good!

Ful not only gets your tongue dancing, it is healthy, and will stick with you for most of the day. It is like throwing a big log on your metabolic fire. No quick burn and crash here, this stuff keeps you going strong.

Ful also makes a great Shabbat dish. Think of it as Egyptian Cholent/Hamin. By simply adding whole eggs in their shell, you achieve a traditional Egyptian Jewish Shabbat meal.

Preparing Ful requires some planning. The beans must be soaked for 24 hours. The dish itself needs to cook for at least 12 hours, but it is better after 18 hours. The good news is that you can make it in a slow cooker overnight. Then it is ready by breakfast time. Once made, the Ful can be stored in the refrigerator for up to a week, and reheated in the microwave as needed. The longer it sits, the better it gets!

Here is the recipe that I use. It is very traditional, but with a few personal touches. This recipe will make quite a large batch, so feel free to cut it in half if you need to.

Ful Muddamas

Ingredients

3 pounds small dried fava beans*, soaked overnight in the refrigerator

1 cup red lentils, rinsed

1 onion, chopped

2 tomatoes, chopped

2 1/2 quarts vegetable stock or water

1 tablespoon hot sauce (your favorite, optional)

1 tablespoon kosher salt (optional, traditionally Ful is not salted until served)

Whole eggs in the shell (optional, for Shabbat)

Directions

1. Place all ingredients into a slow cooker. Cook on High for 2 hours.

2. Turn temperature down to low and cook for 10 to 16 hours.

3. Serve in a bowl with your favorite condiments and plenty of whole grain flat-breads.

If you do not have a slow cooker, start Ful on top of stove in a heavy pot. Bring to a boil, cover, and place in a 200 degree oven for 12 to 18 hours.

Here are some of the traditional garnishes for Ful Mudammas, but feel free to try your own:

hot sauce, olive oil, tahina, hummus, tomato sauce, kashk, butter, garlic sauce, fried egg, hard-cooked egg, chick peas, green onions, and sumac.

* Small fava beans can be found in most Arab or Persian stores, or on-line.

In a pinch, you can substitute regular, brown lentils. This of course is not traditional, and probably will ruffle some purist feathers.February 1, 2011

The Jerusalem Post – January 17, 2011 Photo by: avi katz Jewish Communities have existed in the land of Egypt for thousands of years despite the three prohibitions against returning to Egypt mentioned in the Torah. Egypt has been both a place of “enslavement” and a place of refuge for the Jewish People. All Jews […]

Read more

Posted on

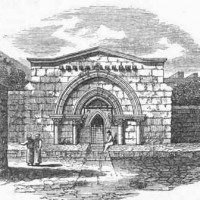

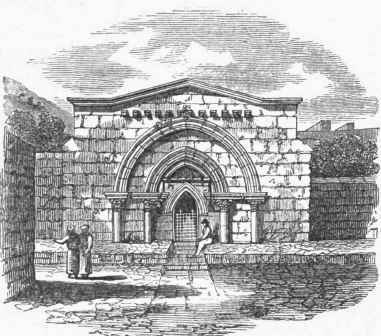

Posted on The rededication of the Rambam Synagogue in Cairo falls victim to cold peace.

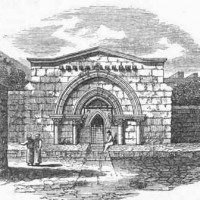

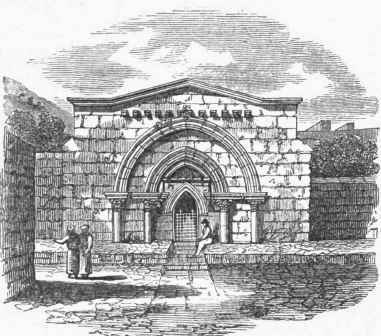

It was a unique occasion. The small yeshiva where 800 years ago Moses Maimonides, the Rambam, taught his disciples had been restored to its pristine state; the synagogue later built on the site, which had fallen into disrepair and had been badly damaged by an earthquake, was once again ready to welcome worshipers.

Egyptian Minister of Culture Farouk Hosny, who had pledged two years ago to renovate three synagogues, had been true to his word. Specialists from the Department of Antiquities had worked long and hard to uncover and duplicate the site’s original colors. The total cost of the project had reached $2 million and the result was spectacular.

All was in place for an impressive ceremony that would have shown the world that Jews and Muslims could rejoice in harmony over a site dedicated to a man held in veneration by both. Maimonides had been the personal physician to Saladin, and for centuries Jews, Muslims and Copts had come to his yeshiva in search of healing. As work was nearing completion, it was agreed with the Egyptian authorities that the small Jewish community of Cairo would organize a dedication ceremony on March 7.

Carmen Weinstein, president of the community, invited Jews from Egypt now living in France, England and other countries as well as a small number of Israelis with special ties to the event such as researchers on the history of the Jews of Egypt and former ambassadors to Egypt. A special invitation had been issued to rabbis of the Chabad movement, for whom the teachings of the Rambam have a great importance; until recently they used to come to the Ben Ezra Synagogue every year at Hanukka.

And then the Egyptians had a change of heart. The head of the Antiquities Department stated that it was an Egyptian site. Let Jews hold a religious ceremony discreetly and among themselves; the official inauguration by the Egyptian authorities would take place a week later. That the decision was both ludicrous and impractical did not occur to them until it was too late.

On March 7, the guests invited by the community made their way to the synagogue. The atmosphere was tense, security personnel and police were present in impressive numbers, surrounding the area and lining the alley leading to the site. The yeshiva and its attendant synagogue are located in what used to be the Jewish Quarter of Cairo.

However, most of the Jews were driven out of Egypt in the ’50s and the ’60s and it has been years since a Jew lived there. The place has turned into a slum; none of its narrow alleys and passageways is asphalted and a layer of tar was hastily applied to the path the visitors would take.

People living there were ordered to close their shops, their doors and their windows and not set foot outside. Security personnel checked invitations and barred journalists from entering. A reporter from a popular daily who tried to interview me was driven away none too gently. A similar fate met a New York Times correspondent. The event was to be kept strictly private – or so hoped the Egyptian authorities. They presumably had not heard of cellphones and other sophisticated recording and transmitting equipment.

Altogether 150 people attended the ceremony, among them Itzhak Lebanon, ambassador of Israel, and Margaret Scobey, the American ambassador, as well as a representative of the Spanish Foreign Ministry who read a message from Miguel Moratinos, who heads Casa de Sefarad, a cultural project concerned with Judeo-Spanish culture, history and tradition – after all the Rambam was born in Cordoba. Speeches were short and non-political; repeated thanks were addressed to the Department of Antiquities and the Ministry of Culture, whose heads were conspicuously absent. The rabbis, who had arrived on the morning flight from Israel and were to return late in the evening, prayed, sang and danced with their usual gusto, urging all present to join them in drinking small cupfuls of vodka. At the end all rose and recited the Shema.

Visitors lingered a little longer. For many, being in the very place the Rambam had taught and prayed was a moving experience. All left with the feeling of having taken part in a very special event.

Meanwhile, the Egyptians who had hoped that the ceremony could be held under wraps were in for a rude awakening. Some of the guests had given interviews to various media in the course of the event. Not many hours lapsed before a video was aired on CNN, and later on the news on Israel’s Channel 2; the Chabad Web site published dozens of photos.

The press in Cairo reacted angrily. Articles and editorials found fault with the presence of the Israeli ambassador, simultaneously bemoaning the amount of money squandered on restoring a Jewish site and declaring the fact that it was a purely Egyptian monument.

Zaki Hawas, head of the Antiquities Department, waded into the fray and declared that “‘Ben Maimon’ would not be handed over to the Jews” and that special measures would be taken to prevent Israelis from visiting in order not to offend Egyptian feelings, in view of the Israeli government’s position on the “Ibrahimi Mosque,” the name given by the Muslim to the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. He added that he had been surprised by the large scale of the event, the participation of the Israeli ambassador and the fact that alcoholic drinks had been imbibed. Therefore, he said, he had taken the decision to cancel the grand opening planned for March 14.

While it would be difficult to see the logic of his arguments, there is no doubt but that he had little choice in the matter. Celebrating the renovation of what is universally known as a Jewish site without any Jewish presence would have given rise to justified criticism. The minister of culture himself said more reasonably that there would be no point in a new event since the dedication ceremony had already been held by the Jewish community.

Thus did Egypt miss a perfect opportunity to show the world that it was an open and tolerant country while reaping political and economic benefits. It chose instead to denigrate the simple and moving ceremony in order to use it as a tool to condemn Israel. True, the ancient yeshiva and the synagogue have been beautifully restored and will stand testimony to the life and work of the Rambam. Yet there is a lingering bitter taste.

The writer is a former Israeli ambassador to Egypt and fellow of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.

Article SourceSeptember 2, 2010

It was a unique occasion. The small yeshiva where 800 years ago Moses Maimonides, the Rambam, taught his disciples had been restored to its pristine state; the synagogue later built on the site, which had fallen into disrepair and had been badly damaged by an earthquake, was once again ready to welcome worshipers.

Egyptian Minister of Culture Farouk Hosny, who had pledged two years ago to renovate three synagogues, had been true to his word. Specialists from the Department of Antiquities had worked long and hard to uncover and duplicate the site’s original colors. The total cost of the project had reached $2 million and the result was spectacular.

All was in place for an impressive ceremony that would have shown the world that Jews and Muslims could rejoice in harmony over a site dedicated to a man held in veneration by both. Maimonides had been the personal physician to Saladin, and for centuries Jews, Muslims and Copts had come to his yeshiva in search of healing. As work was nearing completion, it was agreed with the Egyptian authorities that the small Jewish community of Cairo would organize a dedication ceremony on March 7.

Carmen Weinstein, president of the community, invited Jews from Egypt now living in France, England and other countries as well as a small number of Israelis with special ties to the event such as researchers on the history of the Jews of Egypt and former ambassadors to Egypt. A special invitation had been issued to rabbis of the Chabad movement, for whom the teachings of the Rambam have a great importance; until recently they used to come to the Ben Ezra Synagogue every year at Hanukka.

And then the Egyptians had a change of heart. The head of the Antiquities Department stated that it was an Egyptian site. Let Jews hold a religious ceremony discreetly and among themselves; the official inauguration by the Egyptian authorities would take place a week later. That the decision was both ludicrous and impractical did not occur to them until it was too late.

On March 7, the guests invited by the community made their way to the synagogue. The atmosphere was tense, security personnel and police were present in impressive numbers, surrounding the area and lining the alley leading to the site. The yeshiva and its attendant synagogue are located in what used to be the Jewish Quarter of Cairo.

However, most of the Jews were driven out of Egypt in the ’50s and the ’60s and it has been years since a Jew lived there. The place has turned into a slum; none of its narrow alleys and passageways is asphalted and a layer of tar was hastily applied to the path the visitors would take.

People living there were ordered to close their shops, their doors and their windows and not set foot outside. Security personnel checked invitations and barred journalists from entering. A reporter from a popular daily who tried to interview me was driven away none too gently. A similar fate met a New York Times correspondent. The event was to be kept strictly private – or so hoped the Egyptian authorities. They presumably had not heard of cellphones and other sophisticated recording and transmitting equipment.

Altogether 150 people attended the ceremony, among them Itzhak Lebanon, ambassador of Israel, and Margaret Scobey, the American ambassador, as well as a representative of the Spanish Foreign Ministry who read a message from Miguel Moratinos, who heads Casa de Sefarad, a cultural project concerned with Judeo-Spanish culture, history and tradition – after all the Rambam was born in Cordoba. Speeches were short and non-political; repeated thanks were addressed to the Department of Antiquities and the Ministry of Culture, whose heads were conspicuously absent. The rabbis, who had arrived on the morning flight from Israel and were to return late in the evening, prayed, sang and danced with their usual gusto, urging all present to join them in drinking small cupfuls of vodka. At the end all rose and recited the Shema.

Visitors lingered a little longer. For many, being in the very place the Rambam had taught and prayed was a moving experience. All left with the feeling of having taken part in a very special event.

Meanwhile, the Egyptians who had hoped that the ceremony could be held under wraps were in for a rude awakening. Some of the guests had given interviews to various media in the course of the event. Not many hours lapsed before a video was aired on CNN, and later on the news on Israel’s Channel 2; the Chabad Web site published dozens of photos.

The press in Cairo reacted angrily. Articles and editorials found fault with the presence of the Israeli ambassador, simultaneously bemoaning the amount of money squandered on restoring a Jewish site and declaring the fact that it was a purely Egyptian monument.

Zaki Hawas, head of the Antiquities Department, waded into the fray and declared that “‘Ben Maimon’ would not be handed over to the Jews” and that special measures would be taken to prevent Israelis from visiting in order not to offend Egyptian feelings, in view of the Israeli government’s position on the “Ibrahimi Mosque,” the name given by the Muslim to the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. He added that he had been surprised by the large scale of the event, the participation of the Israeli ambassador and the fact that alcoholic drinks had been imbibed. Therefore, he said, he had taken the decision to cancel the grand opening planned for March 14.

While it would be difficult to see the logic of his arguments, there is no doubt but that he had little choice in the matter. Celebrating the renovation of what is universally known as a Jewish site without any Jewish presence would have given rise to justified criticism. The minister of culture himself said more reasonably that there would be no point in a new event since the dedication ceremony had already been held by the Jewish community.

Thus did Egypt miss a perfect opportunity to show the world that it was an open and tolerant country while reaping political and economic benefits. It chose instead to denigrate the simple and moving ceremony in order to use it as a tool to condemn Israel. True, the ancient yeshiva and the synagogue have been beautifully restored and will stand testimony to the life and work of the Rambam. Yet there is a lingering bitter taste.

The writer is a former Israeli ambassador to Egypt and fellow of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.

Article SourceSeptember 2, 2010

The rededication of the Rambam Synagogue in Cairo falls victim to cold peace. It was a unique occasion. The small yeshiva where 800 years ago Moses Maimonides, the Rambam, taught his disciples had been restored to its pristine state; the synagogue later built on the site, which had fallen into disrepair and had been badly […]

Read more

Posted on The Egyptian government has announced that it will not allow Jews to pray in Cairo's newly-restored Maimonides Synagogue, in retaliation for Israel's security response to Arab rioting on the Temple Mount.

“The Al-Aqsa Mosque is part of the heritage of the Palestinian Arabs and Israel is not entitled to block them from it,” said Dr. Zahi Hawass, Secretary-General of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities.

A Qatari newspaper quoted Hawass in a telephone interview late last week as saying the Maimonides Synagogue would be treated an an Egyptian antiquity, not a Jewish house of worship.

Nor will he allow the Egyptian Jewish community to administer the site – a direct response, he said, to the “provocative practices carried out by the Jews in their celebration which was held in the temple.” Hawass was referring to the wine served at the opening of the synagogue and the joyous dancing with which the celebration was carried out – both practices which he said were offensive to a billion Muslims.

The report “confirmed the temple will not be delivered to the Jewish community in Egypt in any way,” with Hawass stressing that “he would not allow any Jew to pray in the temple, and would not allow any Israeli to pray in the temple.”

Previous reports indicated that Egyptian authorities would allow Jews to pray in the synagogue.

Hawass also denied reports that American Jews had helped pay for the restoration of the synagogue, which he said had cost the Council several million dollars. However, he said, Egypt will continue to restore its ancient synagogues, with the next one to be in Alexandria, the Temple of the Prophet Daniel.

(IsraelNationalNews.com)

Article SourceSeptember 2, 2010

The Egyptian government has announced that it will not allow Jews to pray in Cairo’s newly-restored Maimonides Synagogue, in retaliation for Israel’s security response to Arab rioting on the Temple Mount. “The Al-Aqsa Mosque is part of the heritage of the Palestinian Arabs and Israel is not entitled to block them from it,” said Dr. […]

Read more

Posted on

Posted on  Every year, hundreds of Jews from around the world make a pilgrimage to visit the tomb of a revered rabbi in Egypt’s Nile Delta, located near the Mediterranean port city of Alexandria. This year, tensions between the Israelis and the Palestinians almost spoiled the holy event, scheduled for Saturday, Jan. 9.

Moroccan-born Rabbi Yaakov Abuhatzeira, who died in 1879, is the grandfather of the late Israeli Kabbalist Yisrael Abuhatzeira, better known as the Baba Sali. The tomb of Rabbi Yaakov, who is also known as Abir Yaakov, has become a place of pilgrimage for many hundreds of Jews. Most of the pilgrims arrive from Israel and receive the protection of local security services.

As the date neared for this year’s commemoration of the death of Abuhatzeira, Egypt’s main political movements expressed outrage at their government’s decision to allow Jewish devotees to come to Egypt at a time of high tension between Palestinians and Israelis.

“Visits by Jews shouldn’t happen while Israel continues to impose a choking blockade on the Gaza Strip,” said Mohamed Awad, a member of Egypt’s main protest group Kefaya (Enough). “By allowing these people to come here, our government is betraying the cause of the Palestinians,” he told The Jewish Journal in an interview.

Abuhatzeira’s devotees view him as a pious mystic and miracle worker. He was traveling from Morocco, his country of origin, to the Holy Land when he fell ill and died in the Egyptian village of Damitoh, about 75 miles north of Cairo. A tomb was made for him inside a chamber in the area.

Jewish pilgrims have come to Egypt to visit the tomb and commemorate the death of the rabbi every year since Egypt signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1979.

In recent years, however, Egypt has limited the number of Jewish visitors to the tomb, citing security reasons against the background of increasing tensions between the Israelis and the Palestinians.

In 2009, Egypt denied entry to Jewish pilgrims, because Abuhatzeira’s death anniversary coincided with Israel’s offensive against the Gaza Strip, which is controlled by the Islamist movement of Hamas. Egyptians held nationwide protests against the Israeli offensive.

Late last month, just before the 2010 commemoration of Abuhatzeira, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak reportedly accepted a request from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to hold the commemoration and allow an unlimited number of visitors this year, according to Israeli newspapers.

Near the site of Abuhatzeira’s tomb, thousands of black-clad Egyptian policemen were deployed to guard the event and offer protection to the Jewish pilgrims.

Villagers living near the tomb say they were told to stay home and avoid coming near the place of the celebration.

But such measures haven’t stopped talk in the Egyptian media about the need to prevent this celebration, a demand that rises each year at this time. Some Egyptians have taken the matter to the courts.

In 2001, Mustafa Raslan, an Egyptian lawyer, filed suit against the Egyptian government for allowing Israeli nationals and Jews to come to Egypt for the commemoration. The court ruled to ban the ceremony, ostensibly reacting to public outrage at the event.

Raslan has filed another case to move the remains of Abuhatzeira from Egypt altogether. A verdict is expected in about two weeks.

“We’ll continue to challenge these celebrations and see what happens,” said Gamal Muneib, an Egyptian political activist, who staged a protest against the event together with scores of other activists on Tuesday. “We’ll prevent the buses carrying these Jews to the site of the tomb, even with our bodies,” he added.

Muneib and others have recently formed a new movement to lobby against the Jewish celebration. The movement, called “Over My Land They Won’t Pass,” aims to pressure the government to ban the Abuhatzeira event.

This is a tense time for relations between Egypt and Israel, especially at the public level. A few weeks ago, Egypt started building an underground steel barrier at its border with the Gaza Strip, according to official statements, to block tunnels through which weapons are smuggled. Gaza has been subject to an Israeli blockade since Hamas took over in 2007.

The generally held view in Egypt is that the barrier will choke Hamas and the 1.5 million residents of Gaza, and many believe it is being built at Israel’s behest.

The barrier has ignited a plethora of protests and critical newspaper columns over the last few days. To many in this populous country, Egypt is washing its hands of its role as the big sister of the Arabs, as one columnist put it two days ago.

This sentiment, alongside memories of wars between Egypt and Israel, are being channeled toward the Jewish pilgrims for the Abuhatzeira event.

Despite this, Cairo Airport has seen the arrival of hundreds of Israelis and Jews from Europe and elsewhere over the last few days. The Associated Press reported that as many as 290 arrived at the Cairo airport last Sunday, Jan. 3.

But future visits could be in jeopardy. One Egyptian MP, Zakaria al-Ganayni, plans to raise the issue during the next sessions of the Parliament. He says he will question the government about allowing the Jews to come here to celebrate.

“I’ll also demand a public referendum on the anniversary itself,” he said. “If Egyptians vote ‘No’ to the visits of the Israelis here, we can abolish the event altogether,” he added in statements to the press.

Absent from his mind perhaps was the fact that, prior to the 1952 military coup that toppled the monarchy here, Egypt used to boast a large Jewish community.

The Egyptian capital is home to several Jewish synagogues and many Jewish antiquities, which act as a testament to the harmonious life this country used to have before the coup.

Al-Qotb (“The Writer”) is a pseudonym for The Jewish Journal’s Egyptian correspondent.

Article Source

September 2, 2010

Every year, hundreds of Jews from around the world make a pilgrimage to visit the tomb of a revered rabbi in Egypt’s Nile Delta, located near the Mediterranean port city of Alexandria. This year, tensions between the Israelis and the Palestinians almost spoiled the holy event, scheduled for Saturday, Jan. 9.

Moroccan-born Rabbi Yaakov Abuhatzeira, who died in 1879, is the grandfather of the late Israeli Kabbalist Yisrael Abuhatzeira, better known as the Baba Sali. The tomb of Rabbi Yaakov, who is also known as Abir Yaakov, has become a place of pilgrimage for many hundreds of Jews. Most of the pilgrims arrive from Israel and receive the protection of local security services.

As the date neared for this year’s commemoration of the death of Abuhatzeira, Egypt’s main political movements expressed outrage at their government’s decision to allow Jewish devotees to come to Egypt at a time of high tension between Palestinians and Israelis.

“Visits by Jews shouldn’t happen while Israel continues to impose a choking blockade on the Gaza Strip,” said Mohamed Awad, a member of Egypt’s main protest group Kefaya (Enough). “By allowing these people to come here, our government is betraying the cause of the Palestinians,” he told The Jewish Journal in an interview.

Abuhatzeira’s devotees view him as a pious mystic and miracle worker. He was traveling from Morocco, his country of origin, to the Holy Land when he fell ill and died in the Egyptian village of Damitoh, about 75 miles north of Cairo. A tomb was made for him inside a chamber in the area.

Jewish pilgrims have come to Egypt to visit the tomb and commemorate the death of the rabbi every year since Egypt signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1979.

In recent years, however, Egypt has limited the number of Jewish visitors to the tomb, citing security reasons against the background of increasing tensions between the Israelis and the Palestinians.

In 2009, Egypt denied entry to Jewish pilgrims, because Abuhatzeira’s death anniversary coincided with Israel’s offensive against the Gaza Strip, which is controlled by the Islamist movement of Hamas. Egyptians held nationwide protests against the Israeli offensive.

Late last month, just before the 2010 commemoration of Abuhatzeira, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak reportedly accepted a request from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to hold the commemoration and allow an unlimited number of visitors this year, according to Israeli newspapers.

Near the site of Abuhatzeira’s tomb, thousands of black-clad Egyptian policemen were deployed to guard the event and offer protection to the Jewish pilgrims.

Villagers living near the tomb say they were told to stay home and avoid coming near the place of the celebration.

But such measures haven’t stopped talk in the Egyptian media about the need to prevent this celebration, a demand that rises each year at this time. Some Egyptians have taken the matter to the courts.

In 2001, Mustafa Raslan, an Egyptian lawyer, filed suit against the Egyptian government for allowing Israeli nationals and Jews to come to Egypt for the commemoration. The court ruled to ban the ceremony, ostensibly reacting to public outrage at the event.

Raslan has filed another case to move the remains of Abuhatzeira from Egypt altogether. A verdict is expected in about two weeks.

“We’ll continue to challenge these celebrations and see what happens,” said Gamal Muneib, an Egyptian political activist, who staged a protest against the event together with scores of other activists on Tuesday. “We’ll prevent the buses carrying these Jews to the site of the tomb, even with our bodies,” he added.

Muneib and others have recently formed a new movement to lobby against the Jewish celebration. The movement, called “Over My Land They Won’t Pass,” aims to pressure the government to ban the Abuhatzeira event.

This is a tense time for relations between Egypt and Israel, especially at the public level. A few weeks ago, Egypt started building an underground steel barrier at its border with the Gaza Strip, according to official statements, to block tunnels through which weapons are smuggled. Gaza has been subject to an Israeli blockade since Hamas took over in 2007.

The generally held view in Egypt is that the barrier will choke Hamas and the 1.5 million residents of Gaza, and many believe it is being built at Israel’s behest.

The barrier has ignited a plethora of protests and critical newspaper columns over the last few days. To many in this populous country, Egypt is washing its hands of its role as the big sister of the Arabs, as one columnist put it two days ago.

This sentiment, alongside memories of wars between Egypt and Israel, are being channeled toward the Jewish pilgrims for the Abuhatzeira event.

Despite this, Cairo Airport has seen the arrival of hundreds of Israelis and Jews from Europe and elsewhere over the last few days. The Associated Press reported that as many as 290 arrived at the Cairo airport last Sunday, Jan. 3.

But future visits could be in jeopardy. One Egyptian MP, Zakaria al-Ganayni, plans to raise the issue during the next sessions of the Parliament. He says he will question the government about allowing the Jews to come here to celebrate.

“I’ll also demand a public referendum on the anniversary itself,” he said. “If Egyptians vote ‘No’ to the visits of the Israelis here, we can abolish the event altogether,” he added in statements to the press.

Absent from his mind perhaps was the fact that, prior to the 1952 military coup that toppled the monarchy here, Egypt used to boast a large Jewish community.

The Egyptian capital is home to several Jewish synagogues and many Jewish antiquities, which act as a testament to the harmonious life this country used to have before the coup.

Al-Qotb (“The Writer”) is a pseudonym for The Jewish Journal’s Egyptian correspondent.

Article Source

September 2, 2010

Every year, hundreds of Jews from around the world make a pilgrimage to visit the tomb of a revered rabbi in Egypt’s Nile Delta, located near the Mediterranean port city of Alexandria. This year, tensions between the Israelis and the Palestinians almost spoiled the holy event, scheduled for Saturday, Jan. 9. Moroccan-born Rabbi Yaakov Abuhatzeira, […]

Read more

Photo by: avi katz

Jewish Communities have existed in the land of Egypt for thousands of years despite the three prohibitions against returning to Egypt mentioned in the Torah. Egypt has been both a place of “enslavement” and a place of refuge for the Jewish People. All Jews know the story of the Exodus, but perhaps not everyone knows that Egypt has also been a tolerant safe haven during times of persecution. Wave after wave of Jews settled in Egypt after fleeing or being expelled from other lands. The most notable influx of refugees brought the great Maimonides to Egypt. He and his family were fleeing from the ruthless Almohad Caliphate which conquered portions of Southern Spain and North Africa. Egypt became an important center of Jewish thought, and many Talmudic Schools were established there.

In more recent times, Egypt has also been a place of refuge for Jews fleeing the various pogroms in Europe. The result of all of this immigration was a very large and diverse Jewish Community. Arab Rabbanite, Sephardic, Karaite, and Ashkenazi Communities flourished in Egypt, mostly in the cities of Cairo and Alexandria. By 1922, the Jewish population of Egypt was estimated to be 80,000 people.

And then things changed. During the 1930’s, with the Arab-Jewish fighting in British Occupied Eretz Yisrael and the rise of Nazi Germany, relations between Jewish and Egyptian Society became strained. By the 1940’s, the situation worsened and pogroms took place from 1942 onwards. The founding of the State of Israel in 1948 marked a period of all out war against the Jewish Community. Bombings in Jewish areas claimed 70 lives and injured hundreds more. Riots claimed many more Jewish lives. Jewish property and businesses were confiscated by the Egyptian Government, and Jewish males between the ages of 17 and 60 were forcibly expelled. The Jewish population of Egypt began to dwindle as people fled from their homeland to find refuge in the new State of Israel, Brazil, France, the United States, and Argentina. As of 2004, the Jewish population of Egypt was estimated to be 100 people. The last Jewish wedding in Egypt took place in 1984. To this day, there is strong anti-Jewish sentiment in Egypt, especially in the media. The glory days of the Rambam are no more, and only two synagogues exist in the entire country.

The proud Jews of the Second Exodus have brought their culinary traditions out of Egypt. Their cuisine, like the cuisine of Egypt as a whole, is quite humble and delicious. Grains and legumes figure very prominently in their cooking. Falafel, an Israeli favorite, is Egyptian in origin. Fragrant stews and pulses form the backbone of the cuisine, but there is no shortage of fish, lamb, and poultry dishes. Desserts are ever present and seductively sweet.

Photo by: avi katz

Jewish Communities have existed in the land of Egypt for thousands of years despite the three prohibitions against returning to Egypt mentioned in the Torah. Egypt has been both a place of “enslavement” and a place of refuge for the Jewish People. All Jews know the story of the Exodus, but perhaps not everyone knows that Egypt has also been a tolerant safe haven during times of persecution. Wave after wave of Jews settled in Egypt after fleeing or being expelled from other lands. The most notable influx of refugees brought the great Maimonides to Egypt. He and his family were fleeing from the ruthless Almohad Caliphate which conquered portions of Southern Spain and North Africa. Egypt became an important center of Jewish thought, and many Talmudic Schools were established there.

In more recent times, Egypt has also been a place of refuge for Jews fleeing the various pogroms in Europe. The result of all of this immigration was a very large and diverse Jewish Community. Arab Rabbanite, Sephardic, Karaite, and Ashkenazi Communities flourished in Egypt, mostly in the cities of Cairo and Alexandria. By 1922, the Jewish population of Egypt was estimated to be 80,000 people.

And then things changed. During the 1930’s, with the Arab-Jewish fighting in British Occupied Eretz Yisrael and the rise of Nazi Germany, relations between Jewish and Egyptian Society became strained. By the 1940’s, the situation worsened and pogroms took place from 1942 onwards. The founding of the State of Israel in 1948 marked a period of all out war against the Jewish Community. Bombings in Jewish areas claimed 70 lives and injured hundreds more. Riots claimed many more Jewish lives. Jewish property and businesses were confiscated by the Egyptian Government, and Jewish males between the ages of 17 and 60 were forcibly expelled. The Jewish population of Egypt began to dwindle as people fled from their homeland to find refuge in the new State of Israel, Brazil, France, the United States, and Argentina. As of 2004, the Jewish population of Egypt was estimated to be 100 people. The last Jewish wedding in Egypt took place in 1984. To this day, there is strong anti-Jewish sentiment in Egypt, especially in the media. The glory days of the Rambam are no more, and only two synagogues exist in the entire country.

The proud Jews of the Second Exodus have brought their culinary traditions out of Egypt. Their cuisine, like the cuisine of Egypt as a whole, is quite humble and delicious. Grains and legumes figure very prominently in their cooking. Falafel, an Israeli favorite, is Egyptian in origin. Fragrant stews and pulses form the backbone of the cuisine, but there is no shortage of fish, lamb, and poultry dishes. Desserts are ever present and seductively sweet.